By Bob Thibault

She was the biggest, the most famous, and possibly the most forlorn sailing ship ever stranded in Sea Isle City.

On February 5, 1920, the George R. Skolfield ran aground at 25th Street – which proved to be the undignified end to her final voyage. She wasn’t salvaged. She was left to decay in the sand. She remained buried for a half-century. Then, in the 1970s, what remained of the George R. was finally resurrected and carried away.

Who was George R. Skolfield? What kind of ship carried his name? Where did the ship come from? How did she end up in Sea Isle? And just what happened to her moldering hulk?

The Skolfield family – shipbuilders:

The first George Skolfield was born in July of 1780 in the New England seacoast town of Brunswick, Maine. At the age of 21, he decided that he didn’t particularly care for the life of a farmer and would rather be a shipbuilder. So, with no capital whatsoever, George borrowed money for a broadaxe, set up shop in Brunswick, and proceeded to establish himself in the business. He became known as “Master” George Skolfield.

Master George must have been one fine businessman. During his time, the Skolfield yard built more than 60 ships – square riggers, schooners and sloops – at a rate of about one a year. When he died in 1866, Master George had become one of the wealthiest men in Brunswick.

Along the way, Master George sired eight children including George Rogers Skolfield in 1809. George R., along with two of his brothers, took over the operation of the shipbuilding business on their father’s death.

The Skolfields built wooden ships. They not only built them, but they owned them and sometimes captained them as they sailed around the world. The business prospered until iron and steel vessels started to usurp their prominence in the latter part of the 19th century.

The George R. Skolfield:

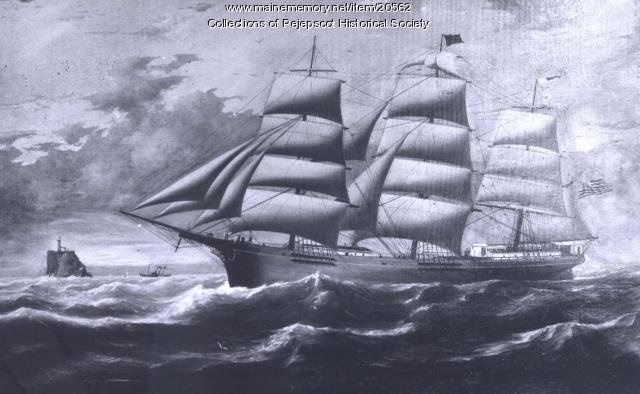

Perhaps as a last hurrah, the Skolfield shipyard launched its largest-ever full-rigged ship in 1885 at a cost of nearly $88,000. Apparently in keeping with family tradition, she was named the George R. Skolfield – complete with George’s own carved likeness as the figurehead.

She was 232 feet long (about the same as a Boeing 747) and weighed in at 1,700 tons. Fittingly, her first voyage was an around-the-world trip. As the pride of the family’s fleet, the George R. regularly carried goods to and from the Orient, and visited ports in Australia, Hawaii, Europe, and the West Indies. But this wasn’t to last.

Her final voyage:

Although the George R. had begun life as a square-rigged sailing ship, she was later converted to a speedier three-masted schooner. A schooner was less expensive to operate, and was intended to compete with the new metal ships.

By the time she headed out on her final voyage, she had been converted again, this time downgraded to what is euphemistically called a “schooner barge” – to be towed sailless up and down the East Coast. It’s a good thing the real George R. Skolfield wasn’t still around.

That last trip began in Fall River, Massachusetts, in early 1920, and was scheduled to terminate in Hampton Roads, Virginia. But on February 5, a violent nor’easter got in the way. The George R. broke her tow in heavy seas, drifted, and was grounded at 25th Street in Sea Isle City.

Her four crew members were safely brought ashore by a surf boat from Sea Isle. After many attempts to re-float the ship, she was finally abandoned, started to break up and sink in the sand – and essentially disappeared. So there she stuck (almost, but not quite) forever.

Resurrection:

On September 10, 1971, a lady named Susan Langston spotted what appeared to be a large chunk of driftwood along the beach in Sea Isle. But it wasn’t exactly driftwood; it was what was left of the George R. Skolfield, newly exposed in the sand.

Even before she knew what she was dealing with, Ms. Langston began the tedious process of claiming the remains, and had them raised and moved on a flatbed truck to a friend’s back yard for storage. The piece weighed about ten tons.

Susan Langston was finally able to identify her find and to arrange for shipment to the Percy and Small Shipyard, a part of the Maine Maritime Museum, for exhibit close to where the human George R. had originally launched her.

(A detailed account of Ms. Langston’s adventure appeared in the American Institute of Nautical Archaeology Newsletter, Winter 1975. The Sea Isle Historical Museum has a copy).

Today, nearly 50 years later, an eight-foot section of the lower hull of the George R. is still on display at the Maine Maritime Museum. The piece is now 134 years old.

The mast and the flagpole:

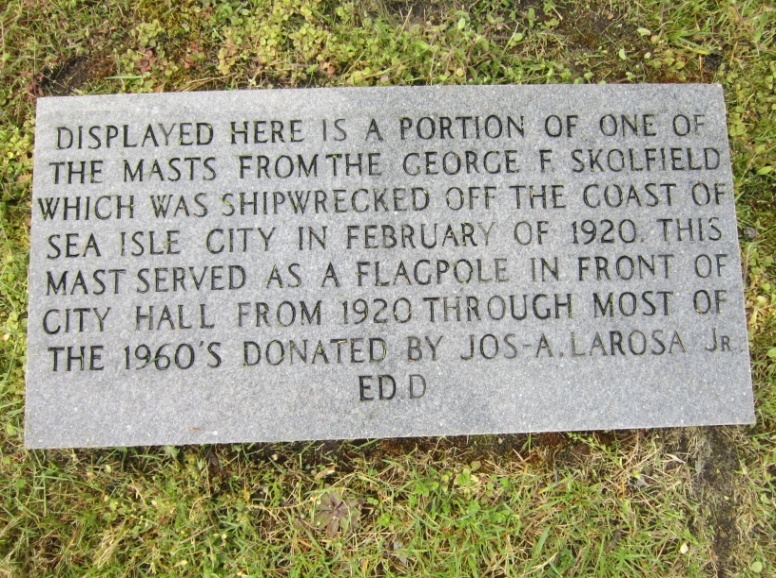

It would be surprising if there aren’t some souvenirs of the ship still tucked away somewhere Sea Isle. The most public example of a relic is the top part of her mast used as the flagpole at the Sea Isle City Historical Museum.

The George R.’s mast didn’t just hop off the dying ship in 1920 and plant itself at the corner of the museum. It was first installed as the City Hall flagpole. Then it was used for forty years to anchor a clothesline at the LaRosa home on Central Avenue. Finally, in 2004, it was donated to the museum.

To take a look at the George R.’s mast, to learn more about early Sea Isle, and to browse through several thousand historic photos, visit the Sea Isle Historical Museum at 48th Street and Central Avenue. Access the website at www.seaislemuseum.com. Call 609-263-2992 with any questions. Hours are 10 a.m. to 3 p.m. on Monday, Tuesday, Thursday and Friday and from 10 a.m. to 1 p.m. on Saturday.

This “Spotlight on History” was written by Sea Isle City Historical Society volunteer Bob Thibault.