Sarah has $340 sitting in a forgotten bank account. She knows it exists, has received two official notices, and yet, three years later, she has done nothing to claim it. This isn’t unusual. Across the U.S., billions of dollars in unclaimed property remain untouched, even when people are fully aware of it.

To traditional economists, this behavior is puzzling. The rational choice theory is based on the premise that people will always act in their own best financial interest. But the fact is more complicated: psychological biases, feelings, and cultural factors tend to prevail over the senses.

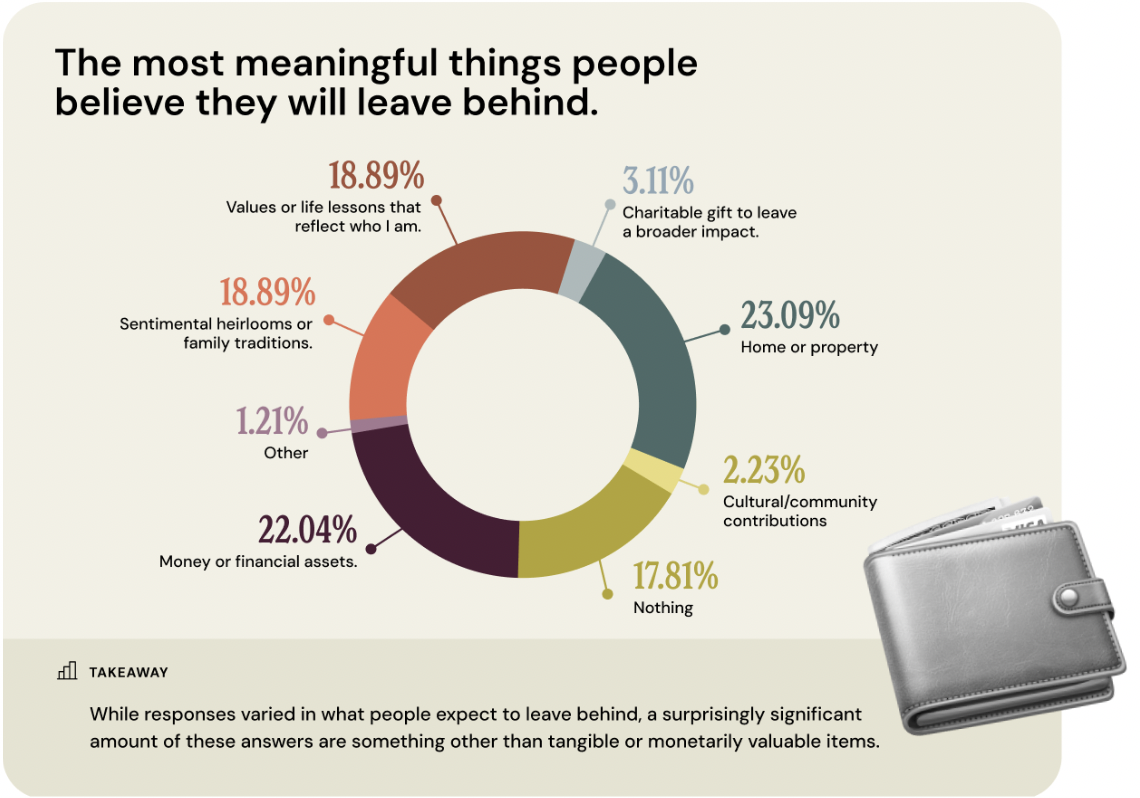

Figure. Survey shows people value leaving behind homes, assets, and life lessons as much as sentimental traditions and values.

The issue of unclaimed property abandonment has nothing to do with laziness, but it deals with human actions. Taking a look at the cognitive, emotional, economic, and social forces that shaped this paradox, we can more clearly explain why so many Americans abandon money that can relieve financial stress.

Behavioral economics reveals that human beings do not act rationally. When it comes to unclaimed property, cognitive biases explain much of the inaction.

Paradoxically, loss aversion, our tendency to avoid losses, backfires. Since unclaimed property is out of sight, most people do not regard it as a loss at all. Status quo bias additionally provides an additional reinforcement of inertia and optimism bias is a belief that makes people think that they are going to take it someday and years go by.

When all these biases are combined, they become a potent cocktail of inaction, and that is why, even highly informed people cannot claim money that is rightfully theirs.

In addition to cognitive shortcuts, emotions have a powerful effect on financial behavior. Most individuals are ashamed of forgetting accounts because they think that it is a sign of irresponsibility. Instead of taking a chance of being embarrassed, they shun action.

The problem is compounded by distrust of government institutions. The community that has a history of exclusion or discrimination tends to look down upon state programs and see them as a trap, and not protection against recovery efforts.

There is also learned helplessness. To individuals who have been trying to navigate through bureaucracy severely, it is assumed that the process is going to be daunting or ineffective. Correspondingly, procrastination and perfectionism do not allow one to begin, particularly when he/she is afraid of error.

It is even made difficult by emotional triggers. Grief may be associated with inherited or deceased-related assets and people may avoid recovery to escape pain. Non-urgent financial activities require a mental energy that stress, depression and family conflict can drain away.

Finally, the issue of unclaimed property abandonment is in many cases not the issue of ignorance, but rather the issue of the emotional value of money and institutions.

The value of an asset shapes behavior more than we admit. People frequently dismiss unclaimed amounts under $50 or $100, assuming the effort outweighs the benefit. This reflects the minimum threshold effect: below a certain mental cutoff, money is coded as "not worth it."

Behavioral economics explains why. People miscalculate transaction costs, assuming paperwork will be harder than it is, while proportional thinking leads them to compare the amount to their larger financial goals, making recovery feel trivial.

This is where support becomes critical. Understanding these psychological barriers to asset recovery is why resources like Claim Notify have become valuable for Americans who recognize the irrationality of abandoning assets but need support overcoming the behavioral and emotional obstacles to recovery.

By reframing small amounts as cumulative wealth and by simplifying processes, individuals can be nudged to reclaim assets that, collectively, represent billions in potential community wealth.

Financial behavior does not occur in a vacuum; culture and community norms matter. In some immigrant households, distrust of authority discourages engagement with government programs, even protective ones. In other families, money is a taboo subject, limiting awareness of forgotten assets.

Behavior is also defined by generational attitudes. The younger generation of adults, who are accustomed to apps and immediate satisfaction, might not be patient with systems that demand a lot of paperwork, and older adults might not afford digital-only access. This is worsened by socio-economic class: more affluent families will hire professional advisors and poorer neighborhoods will be left to sort out complicated procedures on their own.

Even geography plays a role. In rural areas, limited access to banks, advisors, or government offices increases abandonment rates. Meanwhile, peer behavior reinforces norms: if neighbors and family don’t engage with unclaimed property recovery, individuals are less likely to do so themselves.

Knowing these barriers presents an avenue to solutions. According to Nudge theory, behavior can dramatically change if the design is changed a bit. As an illustration, reframing that we are losing, as opposed to getting a bonus, a piece of property that we do not claim can be used to make use of loss aversion in order to be more motivated.

It can also be simplified: the smaller the number of form fields, the pre-filled claims, or mobile submissions, the less cognitive load. Follow-through is made stronger through implementation intentions (If I get a notice, I will file the same day).

There is also the possibility of social proof, where it is pointed out that lots of neighbors have successfully claimed an asset, and this will influence people to do the same. The barriers of emotion can be eliminated by means of trust: better communication, collaboration with communities, and understanding the customers can minimize distrust.

Last but not least, recovery can be fun as gamification trackers or mini-rewards can turn it into an exciting process instead of a boring one. Combined, these behaviorally informed interventions have the potential to turn asset recovery into a bureaucratic liability into an accomplishment and even an inspiring endeavor.

The abandonment of unclaimed property is not irrational but it is human. Negative attitudes, personal feelings, culture and institutional restrictions are all joined together to ensure that Americans never get their back.

Through the application of the psychology concept and behavioral economics, policymakers can create a system of recovery where the people are. Streamlined procedures, compassionate interaction and behavior-based outreach can diminish inertia and enable people.

The practical assistance is offered by such tools as ClaimNotify and it is necessary to encourage citizens to avoid hesitation and recover the wealth that otherwise is lost.

Finally, psychology-policy is not only a bridge to greater recovery rates, but also a more equitable financial system, to one in which human behavior is seen as the most important element in economic design.