If you’ve ever run a project from “interesting hypothesis” to “validated target,” you know how the calendar can quietly disappear. One quarter becomes two. Budgets tighten. A postdoc spends months chasing a gene that turns out to be a bystander. Replicates behave on Monday and misbehave on Thursday. None of this is because the science is sloppy—it’s because the traditional, one-gene-at-a-time playbook is slow and unforgiving.

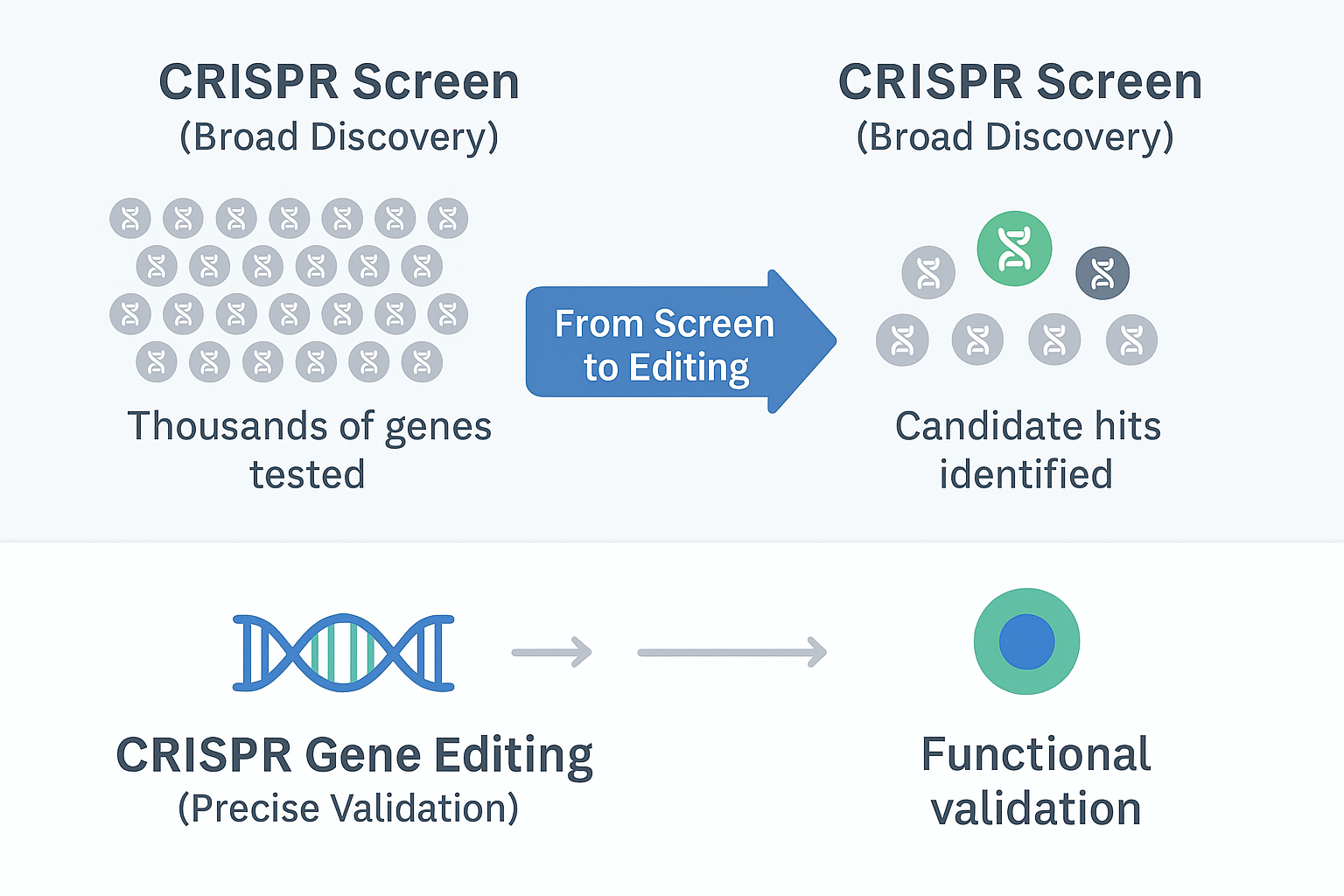

CRISPR screening changes the tempo. Instead of betting everything on a small set of guesses, you perturb thousands of genes in parallel, let the biology speak, and follow the signal. It’s not magic; it’s disciplined triage. Screens won’t write your paper or your IND, but they will tell you where to spend your next week—not your next year. Combined with robust CRISPR editing for follow-up validation, teams can move from “hunch” to “mechanism” with far fewer dead ends.

Below are five ways CRISPR screens are already reshaping day-to-day research—and how to operationalize those gains with practical tools rather than wishful thinking.

Drug discovery starts with a target, and finding that target is often the most expensive part of the journey. The familiar pattern is slow: knock a gene down, measure a phenotype, repeat. Most candidates fade on contact with a functional assay.

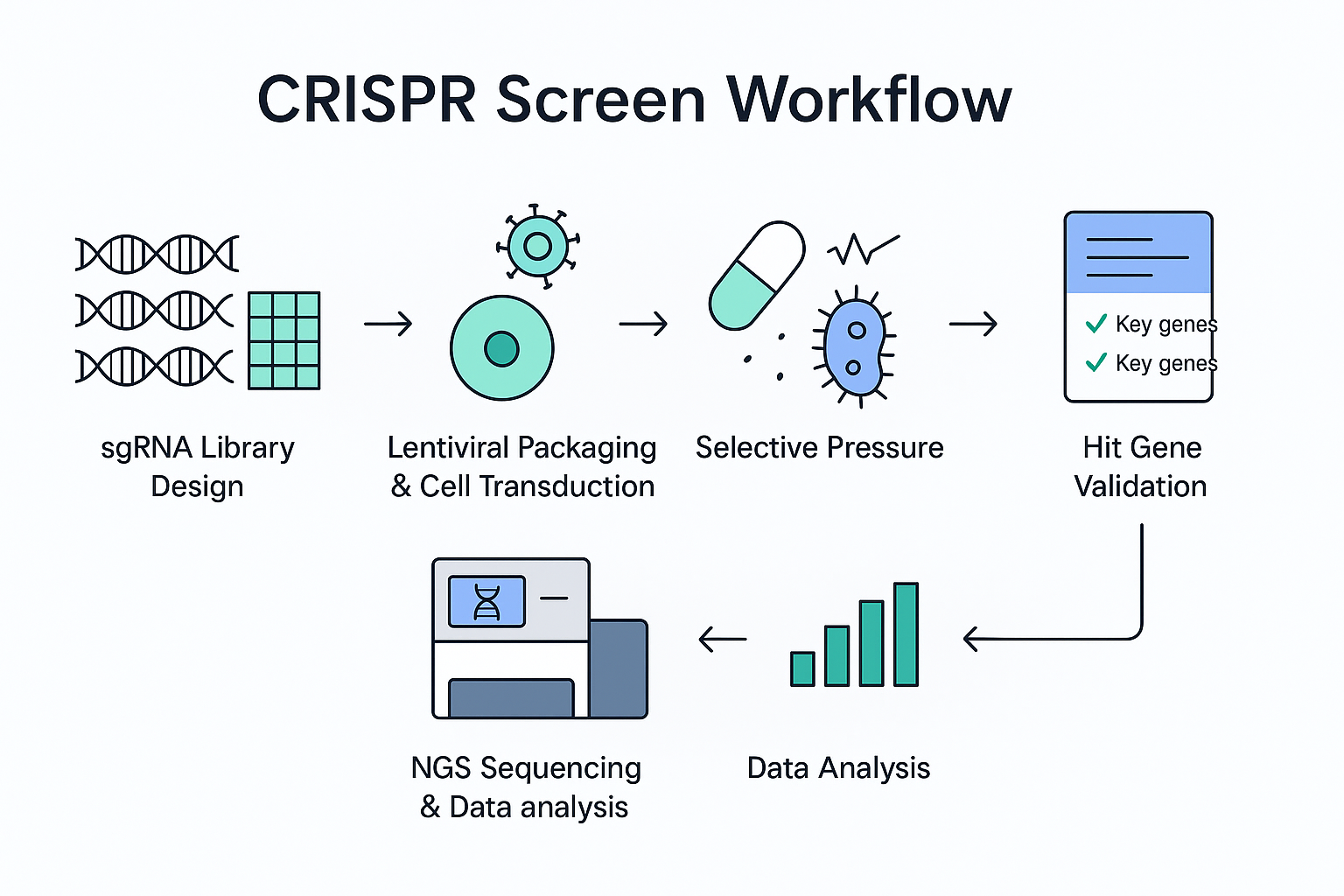

With a well-designed CRISPR screen, you can interrogate an entire pathway—or the whole genome—in one pass. Apply a selective pressure (drug, stress, co-culture), sequence the survivors or dropouts, and rank the genes that truly move your phenotype. The output is not a single “winner” but a sortable, defensible list of hypotheses with effect sizes you can prioritize.

Practical example: In an oncology model, a viability dropout screen highlights a handful of dependencies that are consistently depleted when the tumor cell line is challenged. Instead of testing 200 suspects, your team can focus on the five that actually matter, and run orthogonal assays on those.

How to put it to work: Ubigene’s CRISPR Screening™ Library is available as genome-wide coverage or as focused sub-libraries (e.g., kinases, epigenetic regulators). If you want to see how these libraries can accelerate your project, click here to explore Ubigene’s full range of CRISPR screen solutions. Starting with a ready-to-run library keeps the project moving and avoids months of vector cloning and QC.

Transition: Of course, identifying a promising gene is step one. Next you have to understand what that gene actually does inside the network you care about.

Knowing a gene matters is not the same as knowing how it matters. Pathway context is where many programs slow down: you collect disconnected readouts, and the “story” refuses to cohere.

Screens provide systems-level traction. By coupling pooled perturbations with phenotypes you trust—cell survival, pathway reporters, cytokine readouts, even co-culture behavior—you can sketch the shape of a pathway rather than guessing at individual edges. In immunology, for instance, a reporter-based screen can reveal the upstream regulators of a checkpoint ligand in a single campaign, surfacing both usual suspects and “quiet” genes that rarely appear in literature-driven shortlists.

And this is where robust CRISPR gene editing becomes essential. Once a pathway is mapped, editing tools let you move quickly from pooled hits to single-gene validation—confirming whether a knockout, knock-in, or subtle point mutation truly drives the phenotype. Without that validation step, screens remain only suggestive.

How to put it to work: After a pooled screen narrows the field, you’ll need fast, unambiguous follow-up. Prebuilt CRISPR-U™ Gene Editing Cell Lines (knockout, knock-in, point mutation) let teams move straight into mechanism and epistasis experiments instead of spending weeks engineering models. To explore Ubigene’s broader services in this area, click here and learn how their CRISPR gene editing platform can support everything from KO/KI models to point mutation projects.

Transition: Pathway clarity is essential, but development fails for another, very practical reason: resistance. If screens can explain why a therapy works, they should also help us see why it stops working.

Resistance isn’t a footnote; it is a pipeline risk. Compounds that look excellent in early studies can collapse once cells find a workaround. The old way to study resistance is hypothesis-by-hypothesis. It’s careful—and painfully slow.

Positive-selection CRISPR screens reverse the logic. You apply drug pressure, let the biology select for survivors, and sequence the sgRNAs those survivors carry. The enriched genes point to the pathways that blunt your drug’s effect. You don’t just learn that resistance can happen; you learn how it happens in your exact model, early enough to plan a counter-move.

Practical example: In a targeted therapy program, a pooled screen under chronic dosing identifies a transporter and a signaling adaptor that consistently rise with resistance. That’s a blueprint for rational combination therapy and for biomarker development, not a vague warning that “resistance may occur.”

How to put it to work: Ubigene’s KO Cell Line Bank and Cas9 stable cell lines help you validate resistance hits quickly. Instead of pausing for months to build tools, you can re-create the resistant state or reverse it and confirm causality with clean, comparable models.

Transition: If resistance helps explain why a drug fails, patient heterogeneity helps explain why a drug succeeds for some people but not others.

“Precision medicine” sounds like a marketing phrase until you have to decide whether a specific variant in a specific patient should change your therapy choice. Sequencing gives you a list of mutations; that’s not the same as a functional map.

CRISPR screens provide a practical bridge. By modeling patient-relevant contexts—variant knock-ins, patient-derived cells, organoid systems—you can test how genotype shapes drug response. The question shifts from “Is this variant interesting?” to “Does this variant increase or blunt sensitivity under clinical dosing and timing?”

Practical example: In a rare-disease model, a focused screen across a curated gene set exposes a modifier that flips a drug from “borderline” to “clearly active” in a subset of genotypes. That insight justifies a stratified trial design instead of a blunt, underpowered study.

How to put it to work: Once a screen nominates candidates, you still need to verify single-gene causality at clone resolution. The EZ-editor™ Monoclone Genotype Validation Kit compresses what used to be a multi-day check into less than an hour, so your biology team can keep momentum while the clinical team plans the next decision point.

Transition: Targets shortlisted, pathways mapped, resistance scoped, patient context in hand—now you still have to deliver a program. That means reproducibility and speed.

The longest mile in R&D is often the middle: turning early signals into robust data packages that other teams—and other sites—can reproduce. Many programs stall not because the idea is weak, but because the day-to-day execution is fragile: inconsistent cell health, variable MOI, bottlenecks in assay readiness.

CRISPR screening helps here in two ways. First, it acts as an honest filter so you stop over-investing in ideas that don’t survive first contact with a large, unbiased assay. Second, it forces you to operationalize: you pick a phenotype you trust, you lock down your delivery and coverage, and you build a pipeline that can be re-run.

How to put it to work: The “unsexy” tools are often the ones that keep timelines intact. Media that maintain cell state and freezing solutions that preserve viability aren’t glamorous, but they are the difference between consistent and “almost.” Ubigene’s EZ-Stem™ Cell Culture Medium supports stable growth conditions across campaigns, and EZ-cryo™ Freezing Medium protects precious cell banks for replication and cross-site work. Pair those with disciplined QC on your library and titer, and your second screen will look as good as your first.

CRISPR screens don’t remove the hard parts of biology; they remove the wasteful parts of the process. They help you stop guessing and start ranking. They turn an endless list of “might be important” genes into a small set of “prove me wrong” experiments. And when you pair screening with rigorous CRISPR editing, you build an end-to-end engine for finding, testing, and advancing mechanisms that matter.

For academic labs, this means stronger data and fewer wasted resources. For pharmaceutical teams, it means accelerated timelines and more predictable pipelines. In short, CRISPR screening and editing together are becoming the accelerators modern biomedical research depends on.

Good programs aren’t lucky; they’re well designed. Screens, editing, and a few well-chosen tools make that design easier to execute—and easier to defend.