By BOB THIBAULT

By BOB THIBAULT

Who really owned Sea Isle?

The Players

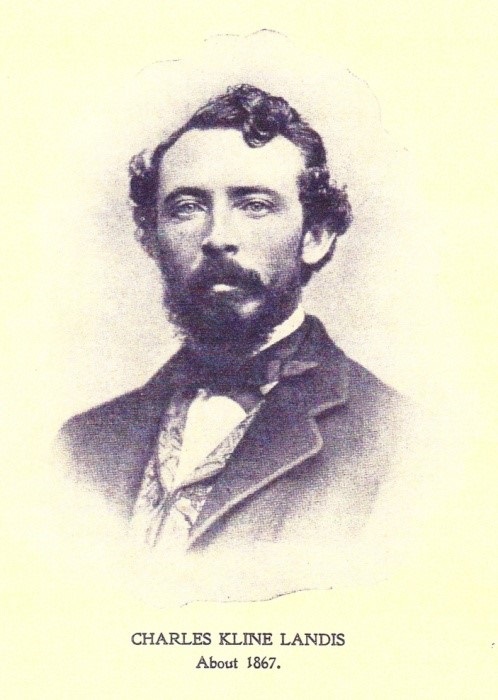

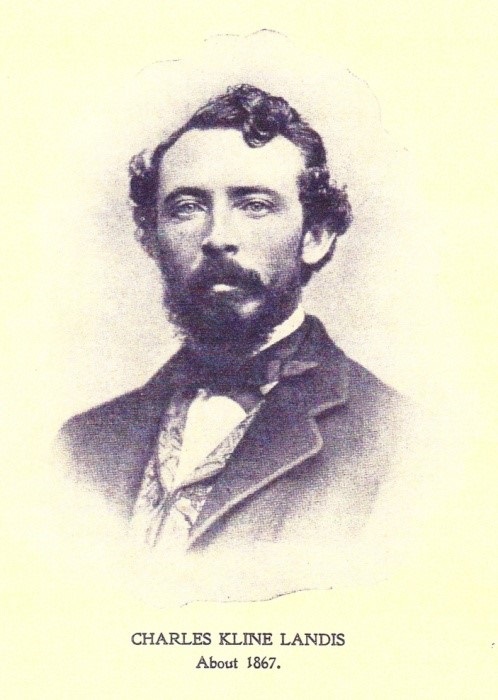

- Charles Kline Landis, founder of Sea Isle, which at one time comprised the whole of Ludlam’s Island,

- Matilda Landis, Charles’s sister, and

- John L. Burk (sometimes “Burke”), who had been Charles Landis’s clerk and private secretary for 14 years when Charles first decided that he was going to own Ludlam’s Island.

There was one pesky obstacle: a great many people already held title to pieces of the land, people who had to be bought out for Charles to realize his goal. Undeterred, he assigned his faithful secretary to go around and do just that.

It sounds fairly simple. But when all was done, Landis had sued Burk, Burk had sued Landis, Matilda had sued both of them, and for a while it wasn’t clear who owned what. The whole mess took seven years to unscramble.

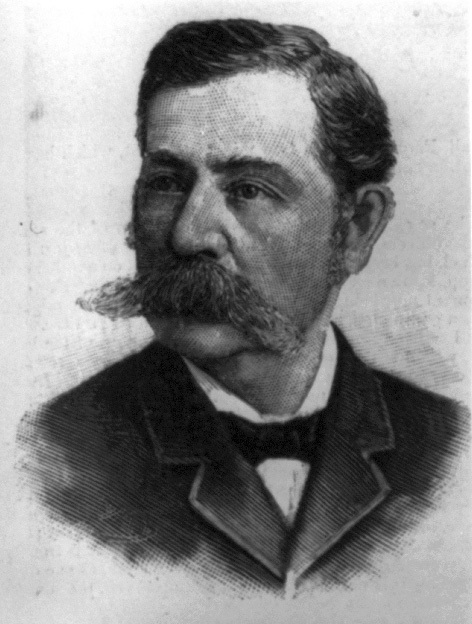

Charles K. Landis – the instigator of the Sea Isle City real estate venture (apparently it was all legal)

Here’s the story, based on information from the Sea Isle City Historical Museum, newspaper articles, title searches, and trial transcripts, with a few conjectures along the way:

The Backstory

Oct 1879: Charles and Matilda Landis agreed that Charles would purchase Ludlam’s Island and register the land in Matilda’s name. According to Charles, if he was listed as the landowner, his creditors (and his wife) might harass him. He authorized John Burk to be his agent in the matter. Matilda provided the odd sum of $1,596 toward securing the needed titles. But she stipulated that whatever compensation Burk received was to be borne by Charles, not her.

Aug 1880: John L. Burk submitted to the Cape May County Clerk, Jonathan Hand, a lengthy list of persons who might hold some of the land on Ludlam’s Island, and requested a search.

Vineland, N.J. Aug 10,1880

Jonathon Hand, Esq.

County Clerk of Cape May County, N.J.

Dear Sir

Please search the records of your Office for Mortgages on the above piece of Land called Ludlams Beach or Island, or any part thereof, against the following names of persons for the time specified

Very Respectfully Yours

John L. Burk

With the researched list in hand, Burk then proceeded to purchase deeds from about 400 people, mostly descendants of the Ludlam, Townsend, and Smith families. He used money forwarded to him by Charles, who went into debt to come up with the cash.

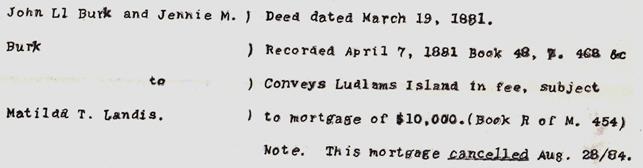

So for a short time, John Burk, along with his wife Jennie, owned the bulk of Ludlam’s Island.

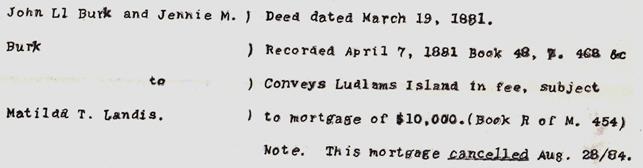

Excerpt from a Title Search conducted in 1886 by L. Newcomb for George Cross.

March 1881: On March 10, a Certificate of Incorporation was filed by the Sea Isle City Improvement Company “to carry on the business of purchasing, improving and selling of land.” Both Landis (president) and Burk (secretary) were Directors of the company. Charles intended to use this as the vehicle for his Ludlam’s Island transactions.

Then on March 19, in accord with their prior agreement, John L. and Jennie M. Burk deeded “all of Ludlam’s Beach or Island” to Matilda T. Landis for a hoped-for consideration of $58,000 for services rendered to the Landis family. (Burk claimed he had never been paid for any of this work.)

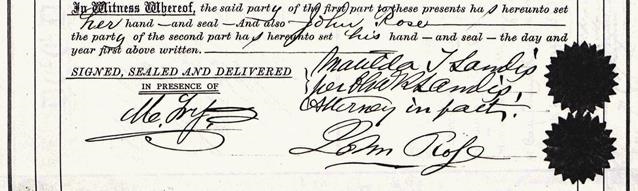

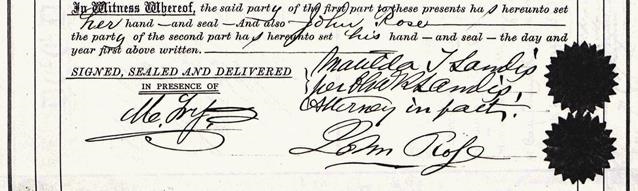

Two days later, Matilda granted Power of Attorney to Charles, granting him the power to sell and convey the land on the island in her name. She granted all proceeds of the property to Charles, after he paid for her costs plus $5,000 cash – plus interest. Here’s an example of such a transaction:

“Matilda T. Landis per Charles K. Landis, Attorney in fact” (in Charles’s hand)

Then the trouble started…

Matilda Landis sues her brother and John Burk

In April of 1881: Charles, on behalf of the absent and unknowing Matilda, agreed with Burk (in writing) to compensate him with $40,000 in stock of the SIC Improvement Company, plus 40 lots in Sea Isle City “south of the railroad.” This would be in lieu of the $58,000 Burk claimed he was owed. Charles figured he was getting off cheaply, because originally he had promised Burke to split the entire venture with him fifty-fifty.

Signatures on a deed from Matilda to John Rose for a parcel of Sea Isle property .

When Matilda found out, she was so unhappy that she filed a suit in the Court of Errors against both men, asking that the agreement between Charles and John Burk be declared void. First, she said it was in excess of Charles’s authority; and second, she claimed that it was procured by Burk by means of fraudulent misrepresentations. She wanted those 40 lots back. Plus, she wanted Burk to receive only about a quarter of that $40,000. It took five years to resolve the issue.

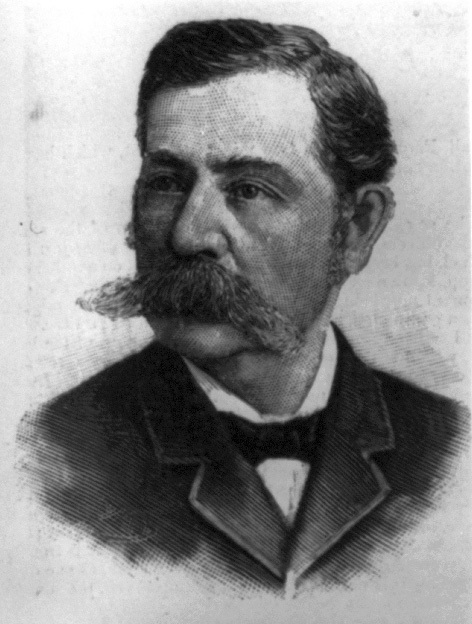

Finally, on February 11, 1886, a verdict was rendered in Matilda’s case by the Chancellor of the State of New Jersey, Theodore Runyan. Besides being Chancellor of New Jersey, Runyan had been a lawyer, mayor of Newark, a Civil War general, and later Ambassador to Germany. He even had a fort named after him. He could certainly handle the litigious trio involved here.

(Just to complicate matters, while Matilda’s suit was progressing, Charles and Burk had entered into their own series of disputes – which annoyed the Chancellor no end.)

Runyan started out by admonishing the codefendants for taking up the time of the court with their own back-and-forth bickering “in matters obviously having no pertinency whatever to the subject of this controversy, and the court has consequently been compelled to spend a great deal of time in reading this impertinent, useless, and often scandalous matter.” They sure knew how to please a judge.

On the other hand, the idyllic photo below of Matilda with Charles and his sons Charles Jr. and Richard was taken during the course of the lawsuit. It seemed there were no hard feelings – which was duly noted by the bemused Court: “Although the suit is certainly against Landis as well as Burk, it is not only thoroughly amicable as far as the former is concerned, but it manifestly is in fact his suit.”

Theodore Runyun. (Photo courtesy of Wikipedia.com)

How did it come out? The compact between the two defendants was upheld. Matilda lost. Her case was dismissed.

The court concluded that “the enterprise was in fact altogether (Charles) Landis’ own, and that he was the principal and not the mere agent.” He, therefore, had every right to do what he did.

So it was much ado about not much, except for the usual lawyers’ fees. In effect, Charles had sued himself and would have won by losing – but he didn’t. And Burk would have been back to square one in his effort to get paid.

The whole issue became further muddled by the ongoing conflict between the two male litigants.

Charles Landis and John Burk Sue Each Other

It began back in 1881. Between April and May of that year some unpleasantness seems to have occurred between Charles and his faithful secretary over Burk’s bookkeeping habits.

In May, Landis announced that all persons having paid money to John Burk (no longer in his employ) were requested to send Landis a written statement “so that the proper entries may be made in (Landis’s) books.”

One may surmise that Burk was selling land mortgages on behalf of Charles and in effect, on behalf of Matilda. Burk may have been a superb secretary and land agent, but he was an acknowledged lousy bookkeeper – and Landis was a bit suspicious. (When Burk disappeared for two weeks, Landis fired him.)

After sifting through a list of deeds made out to Burk, Landis sued his ex-secretary and had him arrested over a particular case. He asserted that Burk had entered into agreement with the Middleton brothers to buy their claim, and in so doing had committed some sort of forgery. He also claimed that Burk owed him $15,000.

Burk was subsequently tried and acquitted. Then, in October, 1883, he turned around and had Landis arrested on a charge of “malicious prosecution and perjury.” He also sued Charles to recover $15,000 in damages. Burk ultimately was granted $432.36.

Officially, Landis was 0-for-2 against Burk. But they weren’t through.

They continued to sue each other and probably would be doing so to this day, if the two of them were still around.

The newspapers of the era describe (unfortunately, with little detail) a more sweeping case, apparently regarding the basic requirement for Landis to meet his commitment to Burk. It seems that Burk prevailed once again, but the enforcement of the agreement had to wait until Matilda’s deal-voiding suit was settled, as described above.

Once Matilda’s suit was dismissed, she began turning over at least some of the specified Sea Isle lots to John Burk – lots which Burk had once deeded to her (in 1881) as part of the original agreement with Charles. The property had been kept in reserve just in case Burk came out the winner – which he did.

(The Sea Isle City Historical Museum has one example of such a transaction where Burk received property from Matilda on August 30, 1886, then turned around and sold it a month later for $600.00. This plot of land sat at the southwest corner of 43rd Street and Marine Place, right on the beach. If that was representative of the location of Burk’s 40 lots, think of what they might be worth today, or even just a few years after Burk acquired them.)

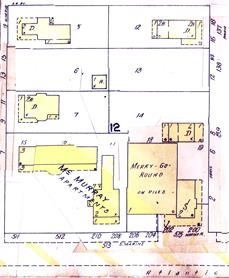

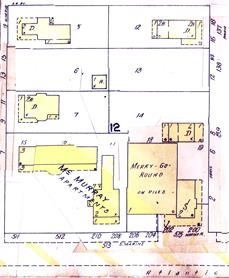

This is the block referenced above, from a survey map dated 1909.

The specific lot in question is where the Merry-Go-Round sat until it was destroyed in the great storm of 1962, and was until lately the site of the Springfield Inn’s seaside Carousel Bar.

But even after all that, Charles Landis and John Burk weren’t through.

Landis continued to sue Burk over “irregularities of Mr. Burk’s accounts,” a case which was still pending in 1886. And in 1887, Burk sued Landis’s Sea Isle City Improvement Co., claiming that he was being mistreated as a shareholder and that the company was insolvent anyway.

It’s not clear how this all turned out, but judging by newspaper reports, there was certainly a lot of suing and countersuing going on – and sometimes it was hard to tell just who was suing whom. The two men, who had been close business associates for many years, ended up not liking each other much at all.

In the end, Charles K. Landis realized his dream for Sea Isle City. Matilda deeded land to Charles, became his agent, a principal heir, and executrix of his will. And John L. Burk seems to have made out like a bandit, which the Landis siblings always claimed he was.

So, in a way, everybody won.

The Sea Isle City Historical Museum is located at 48th Street and Central Avenue. Current hours are 10 a.m. to 3 p.m. Monday, 10 a.m. to Noon Tuesday, 1 p.m. to 3 p.m. Wednesday and Thursday. Access the website at

www.seaislemuseum.com. Call 609-263-2992 for more information.

This Spotlight on History was written by Bob Thibault, a volunteer of the Sea Isle Historical Society.

By BOB THIBAULT

Who really owned Sea Isle?

The Players

By BOB THIBAULT

Who really owned Sea Isle?

The Players

Excerpt from a Title Search conducted in 1886 by L. Newcomb for George Cross.

March 1881: On March 10, a Certificate of Incorporation was filed by the Sea Isle City Improvement Company “to carry on the business of purchasing, improving and selling of land.” Both Landis (president) and Burk (secretary) were Directors of the company. Charles intended to use this as the vehicle for his Ludlam’s Island transactions.

Then on March 19, in accord with their prior agreement, John L. and Jennie M. Burk deeded “all of Ludlam’s Beach or Island” to Matilda T. Landis for a hoped-for consideration of $58,000 for services rendered to the Landis family. (Burk claimed he had never been paid for any of this work.)

Two days later, Matilda granted Power of Attorney to Charles, granting him the power to sell and convey the land on the island in her name. She granted all proceeds of the property to Charles, after he paid for her costs plus $5,000 cash – plus interest. Here’s an example of such a transaction:

“Matilda T. Landis per Charles K. Landis, Attorney in fact” (in Charles’s hand)

Then the trouble started…

Matilda Landis sues her brother and John Burk

In April of 1881: Charles, on behalf of the absent and unknowing Matilda, agreed with Burk (in writing) to compensate him with $40,000 in stock of the SIC Improvement Company, plus 40 lots in Sea Isle City “south of the railroad.” This would be in lieu of the $58,000 Burk claimed he was owed. Charles figured he was getting off cheaply, because originally he had promised Burke to split the entire venture with him fifty-fifty.

Excerpt from a Title Search conducted in 1886 by L. Newcomb for George Cross.

March 1881: On March 10, a Certificate of Incorporation was filed by the Sea Isle City Improvement Company “to carry on the business of purchasing, improving and selling of land.” Both Landis (president) and Burk (secretary) were Directors of the company. Charles intended to use this as the vehicle for his Ludlam’s Island transactions.

Then on March 19, in accord with their prior agreement, John L. and Jennie M. Burk deeded “all of Ludlam’s Beach or Island” to Matilda T. Landis for a hoped-for consideration of $58,000 for services rendered to the Landis family. (Burk claimed he had never been paid for any of this work.)

Two days later, Matilda granted Power of Attorney to Charles, granting him the power to sell and convey the land on the island in her name. She granted all proceeds of the property to Charles, after he paid for her costs plus $5,000 cash – plus interest. Here’s an example of such a transaction:

“Matilda T. Landis per Charles K. Landis, Attorney in fact” (in Charles’s hand)

Then the trouble started…

Matilda Landis sues her brother and John Burk

In April of 1881: Charles, on behalf of the absent and unknowing Matilda, agreed with Burk (in writing) to compensate him with $40,000 in stock of the SIC Improvement Company, plus 40 lots in Sea Isle City “south of the railroad.” This would be in lieu of the $58,000 Burk claimed he was owed. Charles figured he was getting off cheaply, because originally he had promised Burke to split the entire venture with him fifty-fifty.

Signatures on a deed from Matilda to John Rose for a parcel of Sea Isle property .

When Matilda found out, she was so unhappy that she filed a suit in the Court of Errors against both men, asking that the agreement between Charles and John Burk be declared void. First, she said it was in excess of Charles’s authority; and second, she claimed that it was procured by Burk by means of fraudulent misrepresentations. She wanted those 40 lots back. Plus, she wanted Burk to receive only about a quarter of that $40,000. It took five years to resolve the issue.

Finally, on February 11, 1886, a verdict was rendered in Matilda’s case by the Chancellor of the State of New Jersey, Theodore Runyan. Besides being Chancellor of New Jersey, Runyan had been a lawyer, mayor of Newark, a Civil War general, and later Ambassador to Germany. He even had a fort named after him. He could certainly handle the litigious trio involved here.

(Just to complicate matters, while Matilda’s suit was progressing, Charles and Burk had entered into their own series of disputes – which annoyed the Chancellor no end.)

Runyan started out by admonishing the codefendants for taking up the time of the court with their own back-and-forth bickering “in matters obviously having no pertinency whatever to the subject of this controversy, and the court has consequently been compelled to spend a great deal of time in reading this impertinent, useless, and often scandalous matter.” They sure knew how to please a judge.

On the other hand, the idyllic photo below of Matilda with Charles and his sons Charles Jr. and Richard was taken during the course of the lawsuit. It seemed there were no hard feelings – which was duly noted by the bemused Court: “Although the suit is certainly against Landis as well as Burk, it is not only thoroughly amicable as far as the former is concerned, but it manifestly is in fact his suit.”

Signatures on a deed from Matilda to John Rose for a parcel of Sea Isle property .

When Matilda found out, she was so unhappy that she filed a suit in the Court of Errors against both men, asking that the agreement between Charles and John Burk be declared void. First, she said it was in excess of Charles’s authority; and second, she claimed that it was procured by Burk by means of fraudulent misrepresentations. She wanted those 40 lots back. Plus, she wanted Burk to receive only about a quarter of that $40,000. It took five years to resolve the issue.

Finally, on February 11, 1886, a verdict was rendered in Matilda’s case by the Chancellor of the State of New Jersey, Theodore Runyan. Besides being Chancellor of New Jersey, Runyan had been a lawyer, mayor of Newark, a Civil War general, and later Ambassador to Germany. He even had a fort named after him. He could certainly handle the litigious trio involved here.

(Just to complicate matters, while Matilda’s suit was progressing, Charles and Burk had entered into their own series of disputes – which annoyed the Chancellor no end.)

Runyan started out by admonishing the codefendants for taking up the time of the court with their own back-and-forth bickering “in matters obviously having no pertinency whatever to the subject of this controversy, and the court has consequently been compelled to spend a great deal of time in reading this impertinent, useless, and often scandalous matter.” They sure knew how to please a judge.

On the other hand, the idyllic photo below of Matilda with Charles and his sons Charles Jr. and Richard was taken during the course of the lawsuit. It seemed there were no hard feelings – which was duly noted by the bemused Court: “Although the suit is certainly against Landis as well as Burk, it is not only thoroughly amicable as far as the former is concerned, but it manifestly is in fact his suit.”

Theodore Runyun. (Photo courtesy of Wikipedia.com)

How did it come out? The compact between the two defendants was upheld. Matilda lost. Her case was dismissed.

The court concluded that “the enterprise was in fact altogether (Charles) Landis’ own, and that he was the principal and not the mere agent.” He, therefore, had every right to do what he did.

So it was much ado about not much, except for the usual lawyers’ fees. In effect, Charles had sued himself and would have won by losing – but he didn’t. And Burk would have been back to square one in his effort to get paid.

The whole issue became further muddled by the ongoing conflict between the two male litigants.

Charles Landis and John Burk Sue Each Other

It began back in 1881. Between April and May of that year some unpleasantness seems to have occurred between Charles and his faithful secretary over Burk’s bookkeeping habits.

In May, Landis announced that all persons having paid money to John Burk (no longer in his employ) were requested to send Landis a written statement “so that the proper entries may be made in (Landis’s) books.”

One may surmise that Burk was selling land mortgages on behalf of Charles and in effect, on behalf of Matilda. Burk may have been a superb secretary and land agent, but he was an acknowledged lousy bookkeeper – and Landis was a bit suspicious. (When Burk disappeared for two weeks, Landis fired him.)

After sifting through a list of deeds made out to Burk, Landis sued his ex-secretary and had him arrested over a particular case. He asserted that Burk had entered into agreement with the Middleton brothers to buy their claim, and in so doing had committed some sort of forgery. He also claimed that Burk owed him $15,000.

Burk was subsequently tried and acquitted. Then, in October, 1883, he turned around and had Landis arrested on a charge of “malicious prosecution and perjury.” He also sued Charles to recover $15,000 in damages. Burk ultimately was granted $432.36.

Officially, Landis was 0-for-2 against Burk. But they weren’t through.

They continued to sue each other and probably would be doing so to this day, if the two of them were still around.

The newspapers of the era describe (unfortunately, with little detail) a more sweeping case, apparently regarding the basic requirement for Landis to meet his commitment to Burk. It seems that Burk prevailed once again, but the enforcement of the agreement had to wait until Matilda’s deal-voiding suit was settled, as described above.

Once Matilda’s suit was dismissed, she began turning over at least some of the specified Sea Isle lots to John Burk – lots which Burk had once deeded to her (in 1881) as part of the original agreement with Charles. The property had been kept in reserve just in case Burk came out the winner – which he did.

(The Sea Isle City Historical Museum has one example of such a transaction where Burk received property from Matilda on August 30, 1886, then turned around and sold it a month later for $600.00. This plot of land sat at the southwest corner of 43rd Street and Marine Place, right on the beach. If that was representative of the location of Burk’s 40 lots, think of what they might be worth today, or even just a few years after Burk acquired them.)

Theodore Runyun. (Photo courtesy of Wikipedia.com)

How did it come out? The compact between the two defendants was upheld. Matilda lost. Her case was dismissed.

The court concluded that “the enterprise was in fact altogether (Charles) Landis’ own, and that he was the principal and not the mere agent.” He, therefore, had every right to do what he did.

So it was much ado about not much, except for the usual lawyers’ fees. In effect, Charles had sued himself and would have won by losing – but he didn’t. And Burk would have been back to square one in his effort to get paid.

The whole issue became further muddled by the ongoing conflict between the two male litigants.

Charles Landis and John Burk Sue Each Other

It began back in 1881. Between April and May of that year some unpleasantness seems to have occurred between Charles and his faithful secretary over Burk’s bookkeeping habits.

In May, Landis announced that all persons having paid money to John Burk (no longer in his employ) were requested to send Landis a written statement “so that the proper entries may be made in (Landis’s) books.”

One may surmise that Burk was selling land mortgages on behalf of Charles and in effect, on behalf of Matilda. Burk may have been a superb secretary and land agent, but he was an acknowledged lousy bookkeeper – and Landis was a bit suspicious. (When Burk disappeared for two weeks, Landis fired him.)

After sifting through a list of deeds made out to Burk, Landis sued his ex-secretary and had him arrested over a particular case. He asserted that Burk had entered into agreement with the Middleton brothers to buy their claim, and in so doing had committed some sort of forgery. He also claimed that Burk owed him $15,000.

Burk was subsequently tried and acquitted. Then, in October, 1883, he turned around and had Landis arrested on a charge of “malicious prosecution and perjury.” He also sued Charles to recover $15,000 in damages. Burk ultimately was granted $432.36.

Officially, Landis was 0-for-2 against Burk. But they weren’t through.

They continued to sue each other and probably would be doing so to this day, if the two of them were still around.

The newspapers of the era describe (unfortunately, with little detail) a more sweeping case, apparently regarding the basic requirement for Landis to meet his commitment to Burk. It seems that Burk prevailed once again, but the enforcement of the agreement had to wait until Matilda’s deal-voiding suit was settled, as described above.

Once Matilda’s suit was dismissed, she began turning over at least some of the specified Sea Isle lots to John Burk – lots which Burk had once deeded to her (in 1881) as part of the original agreement with Charles. The property had been kept in reserve just in case Burk came out the winner – which he did.

(The Sea Isle City Historical Museum has one example of such a transaction where Burk received property from Matilda on August 30, 1886, then turned around and sold it a month later for $600.00. This plot of land sat at the southwest corner of 43rd Street and Marine Place, right on the beach. If that was representative of the location of Burk’s 40 lots, think of what they might be worth today, or even just a few years after Burk acquired them.)

This is the block referenced above, from a survey map dated 1909.

The specific lot in question is where the Merry-Go-Round sat until it was destroyed in the great storm of 1962, and was until lately the site of the Springfield Inn’s seaside Carousel Bar.

But even after all that, Charles Landis and John Burk weren’t through.

Landis continued to sue Burk over “irregularities of Mr. Burk’s accounts,” a case which was still pending in 1886. And in 1887, Burk sued Landis’s Sea Isle City Improvement Co., claiming that he was being mistreated as a shareholder and that the company was insolvent anyway.

It’s not clear how this all turned out, but judging by newspaper reports, there was certainly a lot of suing and countersuing going on – and sometimes it was hard to tell just who was suing whom. The two men, who had been close business associates for many years, ended up not liking each other much at all.

In the end, Charles K. Landis realized his dream for Sea Isle City. Matilda deeded land to Charles, became his agent, a principal heir, and executrix of his will. And John L. Burk seems to have made out like a bandit, which the Landis siblings always claimed he was.

So, in a way, everybody won.

The Sea Isle City Historical Museum is located at 48th Street and Central Avenue. Current hours are 10 a.m. to 3 p.m. Monday, 10 a.m. to Noon Tuesday, 1 p.m. to 3 p.m. Wednesday and Thursday. Access the website at www.seaislemuseum.com. Call 609-263-2992 for more information.

This Spotlight on History was written by Bob Thibault, a volunteer of the Sea Isle Historical Society.

This is the block referenced above, from a survey map dated 1909.

The specific lot in question is where the Merry-Go-Round sat until it was destroyed in the great storm of 1962, and was until lately the site of the Springfield Inn’s seaside Carousel Bar.

But even after all that, Charles Landis and John Burk weren’t through.

Landis continued to sue Burk over “irregularities of Mr. Burk’s accounts,” a case which was still pending in 1886. And in 1887, Burk sued Landis’s Sea Isle City Improvement Co., claiming that he was being mistreated as a shareholder and that the company was insolvent anyway.

It’s not clear how this all turned out, but judging by newspaper reports, there was certainly a lot of suing and countersuing going on – and sometimes it was hard to tell just who was suing whom. The two men, who had been close business associates for many years, ended up not liking each other much at all.

In the end, Charles K. Landis realized his dream for Sea Isle City. Matilda deeded land to Charles, became his agent, a principal heir, and executrix of his will. And John L. Burk seems to have made out like a bandit, which the Landis siblings always claimed he was.

So, in a way, everybody won.

The Sea Isle City Historical Museum is located at 48th Street and Central Avenue. Current hours are 10 a.m. to 3 p.m. Monday, 10 a.m. to Noon Tuesday, 1 p.m. to 3 p.m. Wednesday and Thursday. Access the website at www.seaislemuseum.com. Call 609-263-2992 for more information.

This Spotlight on History was written by Bob Thibault, a volunteer of the Sea Isle Historical Society.