By BOB THIBAULT

By BOB THIBAULT

They were a corps of citizen-soldiers. The fencibles (short for “defencibles”) were a contingent of volunteers enlisted to perform non-combat duties so that Regular Army soldiers could go fight wars. They sometimes did more, but that was their stated reason for existence.

So, what did these recruits have to do with Sea Isle? According to their own records, they virtually took over the town for a week during the summers of 1908, 1909, and 1910. And they weren’t even from New Jersey. They were from Philadelphia.

Origins

We have the British to thank for the fencible concept. (That’s why it’s spelled with a c.) The first corps was created in Scotland 260 years ago as the Argyle Highland Fencibles and the concept caught on. Fencibles were then raised for the entire British Empire, including Canada. But by the mid-1800s most British fencible units had been formally disbanded, to be replaced by the regular military. (But they were certainly well dressed.)

Meanwhile, on the other side of the Atlantic in 1812, the British were coming – again. The war began a bit slowly, but when the British finally threatened Washington, a hurried call-up of troops ensued. And the deployment of American fencibles seemed sensible.

They called themselves simply the “State Fencibles.” The corps was formed in 1813 when a group of Philadelphians decided they had to do something to protect their city against the British. The first roll of volunteers comprised 78 names and read like a Philadelphia who’s-who. Their motto was: “Let us be judged by our actions.” Their first recorded actions were to march in the Fourth of July parade and attend a banquet.

Just two months after the parade, with no real training, the State Fencibles applied for active service. They were accepted but saw no real action – which may have been just as well. After the War of 1812, the State Fencibles decided to remain together as a corps. They held weekly meetings at a local tavern; honed their military skills; marched in parades; held parties, dinners, receptions and excursions; and conducted lots of target practice. They even incorporated a band in 1821 – one bugle, one fife, and two drums.

State Fencibles uniform (1826)

The fencibles had become both a trained military organization and a social club. Music was written for them. They concocted their own special “Fencibles Punch” to be served at all occasions. (The important ingredients were rum, brandy and champagne.)

The fencibles went on to serve their country and their state for many years, taking part in skirmishes such as the Buckshot War between the governor and his legislature (named after the propellant of choice), the Civil War, and the Spanish-American War. They became one of the best-drilled battalions in the country. But they always seemed to maintain a balance between their military and their social sides.

After the Spanish-American War ended in 1898, things got pretty quiet. What better way to keep sharp in those peaceful times than a stint at summer camp? So, between 1903 and 1907, the fencibles spent ten days each year camping out in places like Stroudsburg and New Hope. Then they discovered Sea Isle.

It isn’t clear just how this out-of-state military battalion came to set up shop in Sea Isle City, but they did – for three years in a row. Again, leaning on the writings of Thomas Lanard, the following is more-or-less what happened.

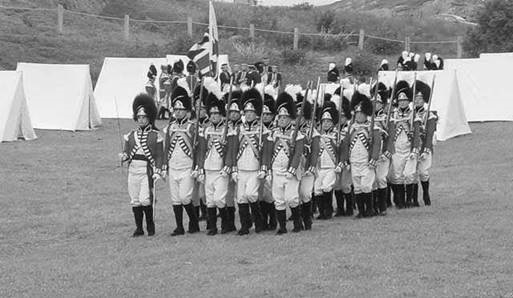

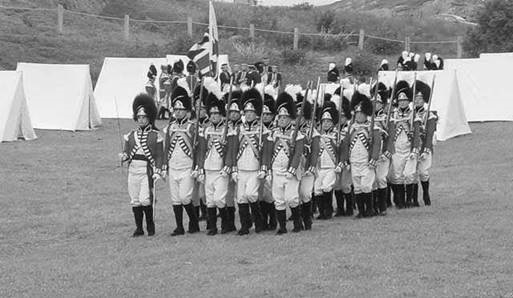

The Royal Newfoundland Fencibles march in formation during a re-enactment.

1908

On August 1, 1908, the fencibles assembled at the Philadelphia armory for their train trip to the shore. They were dressed in service uniforms with olive drab hats and instructed to bring along white pants, black shoes, white gloves, and at least one change of underwear – deemed sufficient for an eight-day stay. The organization must have been impressed by the prospect of camping out in Sea Isle, because they brought the whole battalion with them for the first time since the Spanish-American War.

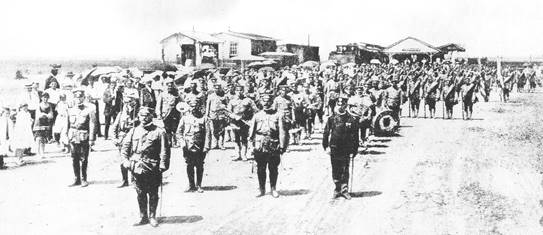

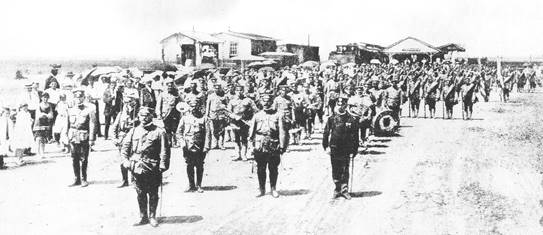

The State Fencibles march into Sea Isle City, led by Commandant Major Thurber T. Brazer, with the West Jersey Railroad Station in the background.

The State Fencibles were impressed with Sea Isle, the citizens of the town became positively smitten by the presence of these “mostly tall and exceedingly well-proportioned” 6 visitors. After a welcoming reception by the American Guards of Sea Isle City and the local Yacht Club, the battalion proceeded to march to their assigned campground, named Camp Kuhn in honor of Hartman Kuhn, the second Captain of the State Fencibles. The site was described by them as “a beautiful tract of land south of the city.”

The tract was actually located on the beach at Prince (56th) Street, but well away from the tourist center of town. In a short time, however, the fencibles were to become their own tourist attraction. It was impossible not to notice a friendly invasion of more than 200 young men in a town of only 550 registered citizens.

The fencibles had a strict daily schedule in Sea Isle from first call at 5:35 am to Taps at 10:30 pm. Those who missed curfew had to peel potatoes. Time was naturally taken up for drills and exercise, but it looks like afternoons were pretty free.

And the fencibles had lots of visitors especially for evening parades and band concerts. But the event of the encampment, and possibly the event of the entire 1908 Sea Isle City season, was the military hop and reception where the hall was decorated military style, the fencibles band performed, and “the lads and their ladies whirled through a program of 20 numbers.”

There was one event so bizarre that it made the New York and Philadelphia papers. On Thursday afternoon, as guests of the Sea Isle City Yacht Club, the fencible officers were taken in four motorboats for a spin on the bay. The little fleet had got as far as Townsend’s Inlet when a wild storm broke, driving three of the craft against a rocky ledge. That was scary – even for the State Fencibles. Enter Robert Drouet.

Drouet was a noted actor and playwright who, for some unexplained reason, was piloting the fourth boat, the Emily. Against the advice of his less adventurous companions, Robert grabbed a tow line in his teeth and swam to the first boat, secured it, then swam back to the Emily, which towed the stricken craft to safety. He repeated this two more times until all were saved and he was totally exhausted. It must have been a riveting show for everyone but Drouet.

In the end, he was feted as a hero and made an honorary member of the Sea Isle City Yacht Club. Maybe he wrote a play about it. It was certainly his greatest performance.

1909

All in all, everyone had collected a positive experience (and a good time) at Camp Hartman Kuhn, so they decided to do it all over again the next year, but with a new bivouac name – Camp Theodore Hesser, in honor of an officer who lost his life during the Civil War. So on July 9, 1909, the State Fencibles mustered in Philadelphia for their return visit to Sea Isle City. By the time they arrived, Mayor Quinn and cheering crowds of citizens were waiting to greet them with fireworks, music and bonfires. (Sea Isle really liked these boys.) By the time they got to camp, it was nearly midnight.

The military routine of the camp – drills, parades, exercises – mirrored the goings-on of the year before, but according to reports, social life ticked up a notch or two. The Battalion gave a military hop at the Excursion House. The Sea Isle City Yacht Club entertained Major Brazer and his staff at the Bellevue. On Saturday night, a ball was held at the Continental Hotel. (Church service and morning drill were canceled the next day.) In lieu of last year’s ill-fated motorboat fiasco, the officers were taken on a much safer auto tour of Tuckahoe, Beasley’s Point and Cape May. And those were just the highlights.

During the day, enlisted men took full advantage of the sand and ocean, ending up as one newspaper reported, with blotches of sun blisters and a blanket of mosquito bites. Sergeant Finscham became so entranced that he wandered 200 yards from shore and had to be rescued by Private Newburg. The private was given the rest of the day off.

Another paper reported that on one occasion sweethearts, wives, sisters and girlfriends stormed the camp, and the infantry immediately laid down their arms and surrendered. After this tough duty, coupled with their real-life military bivouac experience, the State Fencibles decided to return to Sea Isle in 1910.

The State Fencibles in the Spanish-American War.

1910

This time it was to be Camp John Miller, named for another civil war veteran. The Fencibles Battalion reached Sea Isle at 11 p.m. on Friday, August 5. They were met by the City Guards, the local drum corps, and the City officials in a body. It was the signal for a bombardment of cannon crackers, rifle fire and soaring rockets. And according to the Sea Isle Review, “All the pretty girls gathered about the station.” The fencibles marched into town to the tune of ”Dixie,” and when they reached the boardwalk, the promenade was flooded with light. It seems their reception was getting bigger every year.

As in other years, during their nine-day encampment the fencibles performed their approved routine military duties, but found time for relaxation with a large dollop of socializing with the locals. This time the enlisted men were treated to a cruise down the thoroughfare to Avalon and Townsend’s Inlet where, according to the Boardwalk Breeze, “a bevy of pretty girls met the boys...and welcomed them so heartily that it appeared for a while the entire crew would desert ship.“

The highlight of the 1910 season was the Fencibles Ball. It had become an annual event. After the last waltz, the dancers expressed sorrow that they would have to wait a whole year before they could do it all over again. But...

Thereafter

Sadly, there wasn’t to be a next year. By resolution of the State Fencibles Board of Officers, the annual summer camp was abandoned due to funding and preparation needed for a trip to Atlanta in 1911.

The next year there was no encampment because the Battalion was to attend New Haven Week in that city. (It rained on their parade.) Then, in 1913, the entire year was occupied with the one-hundredth anniversary celebration of the State Fencibles’ founding. The organization continued for many years, but there was no return visit to Sea Isle City.

Spotlight on History was written by Sea Isle City Historical Society & Museum volunteer Bob Thibault.

To learn more about Sea Isle’s early history, please visit the Sea Isle City Historical Museum at 48th Street and Central Avenue. Hours are 10-3 Monday, Tuesday, Thursday, and Friday. Access the website at seaislemuseum.com or call 609-263-2992.

By BOB THIBAULT

They were a corps of citizen-soldiers. The fencibles (short for “defencibles”) were a contingent of volunteers enlisted to perform non-combat duties so that Regular Army soldiers could go fight wars. They sometimes did more, but that was their stated reason for existence.

So, what did these recruits have to do with Sea Isle? According to their own records, they virtually took over the town for a week during the summers of 1908, 1909, and 1910. And they weren’t even from New Jersey. They were from Philadelphia.

Origins

We have the British to thank for the fencible concept. (That’s why it’s spelled with a c.) The first corps was created in Scotland 260 years ago as the Argyle Highland Fencibles and the concept caught on. Fencibles were then raised for the entire British Empire, including Canada. But by the mid-1800s most British fencible units had been formally disbanded, to be replaced by the regular military. (But they were certainly well dressed.)

Meanwhile, on the other side of the Atlantic in 1812, the British were coming – again. The war began a bit slowly, but when the British finally threatened Washington, a hurried call-up of troops ensued. And the deployment of American fencibles seemed sensible.

They called themselves simply the “State Fencibles.” The corps was formed in 1813 when a group of Philadelphians decided they had to do something to protect their city against the British. The first roll of volunteers comprised 78 names and read like a Philadelphia who’s-who. Their motto was: “Let us be judged by our actions.” Their first recorded actions were to march in the Fourth of July parade and attend a banquet.

Just two months after the parade, with no real training, the State Fencibles applied for active service. They were accepted but saw no real action – which may have been just as well. After the War of 1812, the State Fencibles decided to remain together as a corps. They held weekly meetings at a local tavern; honed their military skills; marched in parades; held parties, dinners, receptions and excursions; and conducted lots of target practice. They even incorporated a band in 1821 – one bugle, one fife, and two drums.

State Fencibles uniform (1826)

The fencibles had become both a trained military organization and a social club. Music was written for them. They concocted their own special “Fencibles Punch” to be served at all occasions. (The important ingredients were rum, brandy and champagne.)

The fencibles went on to serve their country and their state for many years, taking part in skirmishes such as the Buckshot War between the governor and his legislature (named after the propellant of choice), the Civil War, and the Spanish-American War. They became one of the best-drilled battalions in the country. But they always seemed to maintain a balance between their military and their social sides.

After the Spanish-American War ended in 1898, things got pretty quiet. What better way to keep sharp in those peaceful times than a stint at summer camp? So, between 1903 and 1907, the fencibles spent ten days each year camping out in places like Stroudsburg and New Hope. Then they discovered Sea Isle.

It isn’t clear just how this out-of-state military battalion came to set up shop in Sea Isle City, but they did – for three years in a row. Again, leaning on the writings of Thomas Lanard, the following is more-or-less what happened.

By BOB THIBAULT

They were a corps of citizen-soldiers. The fencibles (short for “defencibles”) were a contingent of volunteers enlisted to perform non-combat duties so that Regular Army soldiers could go fight wars. They sometimes did more, but that was their stated reason for existence.

So, what did these recruits have to do with Sea Isle? According to their own records, they virtually took over the town for a week during the summers of 1908, 1909, and 1910. And they weren’t even from New Jersey. They were from Philadelphia.

Origins

We have the British to thank for the fencible concept. (That’s why it’s spelled with a c.) The first corps was created in Scotland 260 years ago as the Argyle Highland Fencibles and the concept caught on. Fencibles were then raised for the entire British Empire, including Canada. But by the mid-1800s most British fencible units had been formally disbanded, to be replaced by the regular military. (But they were certainly well dressed.)

Meanwhile, on the other side of the Atlantic in 1812, the British were coming – again. The war began a bit slowly, but when the British finally threatened Washington, a hurried call-up of troops ensued. And the deployment of American fencibles seemed sensible.

They called themselves simply the “State Fencibles.” The corps was formed in 1813 when a group of Philadelphians decided they had to do something to protect their city against the British. The first roll of volunteers comprised 78 names and read like a Philadelphia who’s-who. Their motto was: “Let us be judged by our actions.” Their first recorded actions were to march in the Fourth of July parade and attend a banquet.

Just two months after the parade, with no real training, the State Fencibles applied for active service. They were accepted but saw no real action – which may have been just as well. After the War of 1812, the State Fencibles decided to remain together as a corps. They held weekly meetings at a local tavern; honed their military skills; marched in parades; held parties, dinners, receptions and excursions; and conducted lots of target practice. They even incorporated a band in 1821 – one bugle, one fife, and two drums.

State Fencibles uniform (1826)

The fencibles had become both a trained military organization and a social club. Music was written for them. They concocted their own special “Fencibles Punch” to be served at all occasions. (The important ingredients were rum, brandy and champagne.)

The fencibles went on to serve their country and their state for many years, taking part in skirmishes such as the Buckshot War between the governor and his legislature (named after the propellant of choice), the Civil War, and the Spanish-American War. They became one of the best-drilled battalions in the country. But they always seemed to maintain a balance between their military and their social sides.

After the Spanish-American War ended in 1898, things got pretty quiet. What better way to keep sharp in those peaceful times than a stint at summer camp? So, between 1903 and 1907, the fencibles spent ten days each year camping out in places like Stroudsburg and New Hope. Then they discovered Sea Isle.

It isn’t clear just how this out-of-state military battalion came to set up shop in Sea Isle City, but they did – for three years in a row. Again, leaning on the writings of Thomas Lanard, the following is more-or-less what happened.

The Royal Newfoundland Fencibles march in formation during a re-enactment.

1908

On August 1, 1908, the fencibles assembled at the Philadelphia armory for their train trip to the shore. They were dressed in service uniforms with olive drab hats and instructed to bring along white pants, black shoes, white gloves, and at least one change of underwear – deemed sufficient for an eight-day stay. The organization must have been impressed by the prospect of camping out in Sea Isle, because they brought the whole battalion with them for the first time since the Spanish-American War.

The State Fencibles march into Sea Isle City, led by Commandant Major Thurber T. Brazer, with the West Jersey Railroad Station in the background.

The State Fencibles were impressed with Sea Isle, the citizens of the town became positively smitten by the presence of these “mostly tall and exceedingly well-proportioned” 6 visitors. After a welcoming reception by the American Guards of Sea Isle City and the local Yacht Club, the battalion proceeded to march to their assigned campground, named Camp Kuhn in honor of Hartman Kuhn, the second Captain of the State Fencibles. The site was described by them as “a beautiful tract of land south of the city.”

The tract was actually located on the beach at Prince (56th) Street, but well away from the tourist center of town. In a short time, however, the fencibles were to become their own tourist attraction. It was impossible not to notice a friendly invasion of more than 200 young men in a town of only 550 registered citizens.

The fencibles had a strict daily schedule in Sea Isle from first call at 5:35 am to Taps at 10:30 pm. Those who missed curfew had to peel potatoes. Time was naturally taken up for drills and exercise, but it looks like afternoons were pretty free.

And the fencibles had lots of visitors especially for evening parades and band concerts. But the event of the encampment, and possibly the event of the entire 1908 Sea Isle City season, was the military hop and reception where the hall was decorated military style, the fencibles band performed, and “the lads and their ladies whirled through a program of 20 numbers.”

There was one event so bizarre that it made the New York and Philadelphia papers. On Thursday afternoon, as guests of the Sea Isle City Yacht Club, the fencible officers were taken in four motorboats for a spin on the bay. The little fleet had got as far as Townsend’s Inlet when a wild storm broke, driving three of the craft against a rocky ledge. That was scary – even for the State Fencibles. Enter Robert Drouet.

Drouet was a noted actor and playwright who, for some unexplained reason, was piloting the fourth boat, the Emily. Against the advice of his less adventurous companions, Robert grabbed a tow line in his teeth and swam to the first boat, secured it, then swam back to the Emily, which towed the stricken craft to safety. He repeated this two more times until all were saved and he was totally exhausted. It must have been a riveting show for everyone but Drouet.

In the end, he was feted as a hero and made an honorary member of the Sea Isle City Yacht Club. Maybe he wrote a play about it. It was certainly his greatest performance.

The Royal Newfoundland Fencibles march in formation during a re-enactment.

1908

On August 1, 1908, the fencibles assembled at the Philadelphia armory for their train trip to the shore. They were dressed in service uniforms with olive drab hats and instructed to bring along white pants, black shoes, white gloves, and at least one change of underwear – deemed sufficient for an eight-day stay. The organization must have been impressed by the prospect of camping out in Sea Isle, because they brought the whole battalion with them for the first time since the Spanish-American War.

The State Fencibles march into Sea Isle City, led by Commandant Major Thurber T. Brazer, with the West Jersey Railroad Station in the background.

The State Fencibles were impressed with Sea Isle, the citizens of the town became positively smitten by the presence of these “mostly tall and exceedingly well-proportioned” 6 visitors. After a welcoming reception by the American Guards of Sea Isle City and the local Yacht Club, the battalion proceeded to march to their assigned campground, named Camp Kuhn in honor of Hartman Kuhn, the second Captain of the State Fencibles. The site was described by them as “a beautiful tract of land south of the city.”

The tract was actually located on the beach at Prince (56th) Street, but well away from the tourist center of town. In a short time, however, the fencibles were to become their own tourist attraction. It was impossible not to notice a friendly invasion of more than 200 young men in a town of only 550 registered citizens.

The fencibles had a strict daily schedule in Sea Isle from first call at 5:35 am to Taps at 10:30 pm. Those who missed curfew had to peel potatoes. Time was naturally taken up for drills and exercise, but it looks like afternoons were pretty free.

And the fencibles had lots of visitors especially for evening parades and band concerts. But the event of the encampment, and possibly the event of the entire 1908 Sea Isle City season, was the military hop and reception where the hall was decorated military style, the fencibles band performed, and “the lads and their ladies whirled through a program of 20 numbers.”

There was one event so bizarre that it made the New York and Philadelphia papers. On Thursday afternoon, as guests of the Sea Isle City Yacht Club, the fencible officers were taken in four motorboats for a spin on the bay. The little fleet had got as far as Townsend’s Inlet when a wild storm broke, driving three of the craft against a rocky ledge. That was scary – even for the State Fencibles. Enter Robert Drouet.

Drouet was a noted actor and playwright who, for some unexplained reason, was piloting the fourth boat, the Emily. Against the advice of his less adventurous companions, Robert grabbed a tow line in his teeth and swam to the first boat, secured it, then swam back to the Emily, which towed the stricken craft to safety. He repeated this two more times until all were saved and he was totally exhausted. It must have been a riveting show for everyone but Drouet.

In the end, he was feted as a hero and made an honorary member of the Sea Isle City Yacht Club. Maybe he wrote a play about it. It was certainly his greatest performance.

The State Fencibles in the Spanish-American War.

1910

This time it was to be Camp John Miller, named for another civil war veteran. The Fencibles Battalion reached Sea Isle at 11 p.m. on Friday, August 5. They were met by the City Guards, the local drum corps, and the City officials in a body. It was the signal for a bombardment of cannon crackers, rifle fire and soaring rockets. And according to the Sea Isle Review, “All the pretty girls gathered about the station.” The fencibles marched into town to the tune of ”Dixie,” and when they reached the boardwalk, the promenade was flooded with light. It seems their reception was getting bigger every year.

As in other years, during their nine-day encampment the fencibles performed their approved routine military duties, but found time for relaxation with a large dollop of socializing with the locals. This time the enlisted men were treated to a cruise down the thoroughfare to Avalon and Townsend’s Inlet where, according to the Boardwalk Breeze, “a bevy of pretty girls met the boys...and welcomed them so heartily that it appeared for a while the entire crew would desert ship.“

The highlight of the 1910 season was the Fencibles Ball. It had become an annual event. After the last waltz, the dancers expressed sorrow that they would have to wait a whole year before they could do it all over again. But...

Thereafter

Sadly, there wasn’t to be a next year. By resolution of the State Fencibles Board of Officers, the annual summer camp was abandoned due to funding and preparation needed for a trip to Atlanta in 1911.

The next year there was no encampment because the Battalion was to attend New Haven Week in that city. (It rained on their parade.) Then, in 1913, the entire year was occupied with the one-hundredth anniversary celebration of the State Fencibles’ founding. The organization continued for many years, but there was no return visit to Sea Isle City.

Spotlight on History was written by Sea Isle City Historical Society & Museum volunteer Bob Thibault.

To learn more about Sea Isle’s early history, please visit the Sea Isle City Historical Museum at 48th Street and Central Avenue. Hours are 10-3 Monday, Tuesday, Thursday, and Friday. Access the website at seaislemuseum.com or call 609-263-2992.

The State Fencibles in the Spanish-American War.

1910

This time it was to be Camp John Miller, named for another civil war veteran. The Fencibles Battalion reached Sea Isle at 11 p.m. on Friday, August 5. They were met by the City Guards, the local drum corps, and the City officials in a body. It was the signal for a bombardment of cannon crackers, rifle fire and soaring rockets. And according to the Sea Isle Review, “All the pretty girls gathered about the station.” The fencibles marched into town to the tune of ”Dixie,” and when they reached the boardwalk, the promenade was flooded with light. It seems their reception was getting bigger every year.

As in other years, during their nine-day encampment the fencibles performed their approved routine military duties, but found time for relaxation with a large dollop of socializing with the locals. This time the enlisted men were treated to a cruise down the thoroughfare to Avalon and Townsend’s Inlet where, according to the Boardwalk Breeze, “a bevy of pretty girls met the boys...and welcomed them so heartily that it appeared for a while the entire crew would desert ship.“

The highlight of the 1910 season was the Fencibles Ball. It had become an annual event. After the last waltz, the dancers expressed sorrow that they would have to wait a whole year before they could do it all over again. But...

Thereafter

Sadly, there wasn’t to be a next year. By resolution of the State Fencibles Board of Officers, the annual summer camp was abandoned due to funding and preparation needed for a trip to Atlanta in 1911.

The next year there was no encampment because the Battalion was to attend New Haven Week in that city. (It rained on their parade.) Then, in 1913, the entire year was occupied with the one-hundredth anniversary celebration of the State Fencibles’ founding. The organization continued for many years, but there was no return visit to Sea Isle City.

Spotlight on History was written by Sea Isle City Historical Society & Museum volunteer Bob Thibault.

To learn more about Sea Isle’s early history, please visit the Sea Isle City Historical Museum at 48th Street and Central Avenue. Hours are 10-3 Monday, Tuesday, Thursday, and Friday. Access the website at seaislemuseum.com or call 609-263-2992.