Similar to the Sea Isle serpent, this one was spotted three times in 1897 off Little Gull Island in Long Island Sound. (Images provided by the Sea Isle City Historical Museum)

By BOB THIBAULT

On an otherwise normal Thursday in May 1886, a remarkable event occurred in Sea Isle City. The borough was visited by a massive SEA SERPENT – right there on the beach at Townsends Inlet.

There are no photos or contemporary sketches of the creature, but a frighteningly detailed description appeared in the Philadelphia News a week later.

The scene was described by two independent sets of observers at different times of day, observers who weren’t aware of the existence of one another. That seems to give the story at least a modicum of validity. Something happened.

Some Serpent Lore

Do sea serpents really exist? As far back as 2,000 years ago, Virgil spoke of seeing a matched pair of serpents with fiery eyes and hissing tongues. And the number of sightings grew through the years.

But it wasn’t until the 18th and 19th centuries when sailors, possibly encouraged by a little grog, began to spot them all over the place.

The first memorable event on the eastern seaboard of the U.S. occurred in 1817 when the “Gloucester Serpent” was observed frolicking offshore in the Gulf of Maine. It appeared intermittently for three years in a row, including forays up and down the Atlantic Coast.

This guy – they were all called “guys” in those days – was described as 60 to 80 feet long with a head like a horse, and looked pretty much like an overgrown snake. He was observed by hundreds of people, including the renowned Daniel Webster, all of whom swore that the creature was authentic. Scientists even gave him a name (“Scoliophis Atlanticus”) and declared him to be a whole new species.

And so it went. The number of serpents sighted in the 19th century probably counted into the hundreds and reached a peak in the 1880s and 1890s. P.T. Barnum once offered $20,000 to anyone who could provide him with the genuine article, but it appears he never had to lay out the cash.

New Jersey Had Its Share

When a sea serpent popped up in Sea Isle City in 1886, it was not a unique occurrence for the Garden State. Some examples of contemporary Jersey sightings:

By BOB THIBAULT

On an otherwise normal Thursday in May 1886, a remarkable event occurred in Sea Isle City. The borough was visited by a massive SEA SERPENT – right there on the beach at Townsends Inlet.

There are no photos or contemporary sketches of the creature, but a frighteningly detailed description appeared in the Philadelphia News a week later.

The scene was described by two independent sets of observers at different times of day, observers who weren’t aware of the existence of one another. That seems to give the story at least a modicum of validity. Something happened.

Some Serpent Lore

Do sea serpents really exist? As far back as 2,000 years ago, Virgil spoke of seeing a matched pair of serpents with fiery eyes and hissing tongues. And the number of sightings grew through the years.

But it wasn’t until the 18th and 19th centuries when sailors, possibly encouraged by a little grog, began to spot them all over the place.

The first memorable event on the eastern seaboard of the U.S. occurred in 1817 when the “Gloucester Serpent” was observed frolicking offshore in the Gulf of Maine. It appeared intermittently for three years in a row, including forays up and down the Atlantic Coast.

This guy – they were all called “guys” in those days – was described as 60 to 80 feet long with a head like a horse, and looked pretty much like an overgrown snake. He was observed by hundreds of people, including the renowned Daniel Webster, all of whom swore that the creature was authentic. Scientists even gave him a name (“Scoliophis Atlanticus”) and declared him to be a whole new species.

And so it went. The number of serpents sighted in the 19th century probably counted into the hundreds and reached a peak in the 1880s and 1890s. P.T. Barnum once offered $20,000 to anyone who could provide him with the genuine article, but it appears he never had to lay out the cash.

New Jersey Had Its Share

When a sea serpent popped up in Sea Isle City in 1886, it was not a unique occurrence for the Garden State. Some examples of contemporary Jersey sightings:

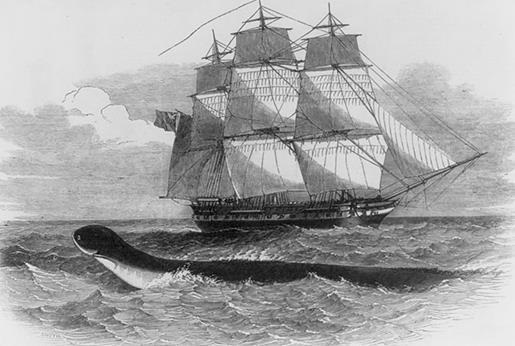

The Daedalus and its ubiquitous Sea Serpent (Gleason’s Pictorial Drawing Room Companion, July, 1852)

Closer to Home

The Daedalus and its ubiquitous Sea Serpent (Gleason’s Pictorial Drawing Room Companion, July, 1852)

Closer to Home

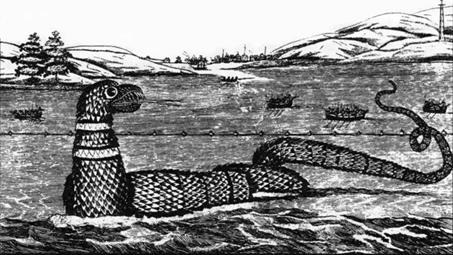

The Gloucester Sea Serpent (Ellis, R. 1994 “Monsters of the Sea” Robert Hale Ltd.)

The entire troupe jumped out of the wagon to have a better look. In Ellis’s own words: “It had a head something like that of a catfish in shape, only the mouth was V-shaped in the middle and underneath was a long reddish beard. The color of the head was a sort of fawn and right in the middle of the forehead there was a circular patch of transparent skin, which at first looked like a gigantic eye.”

But when Ellis produced a pair of opera glasses, he had a better look at that transparent patch which sat about 12 inches above the mouth. Again, in his own words:

“I could distinctly see ... the pulsating of the creature’s brain through that window of clear skin,” an interpretation verified by Mr. Gaines and Mr. Smith. Ellis went on to say that the monster sported a pair of wings or fins which, when extended, “stood out like the sails of a small yacht.”

Now the adventurers wanted an even closer view, so they started to advance “at a brisk pace.” This apparently unnerved the beast and it turned broadside to expose three webbed feet, each about three feet in diameter. The body appeared to be about “a hogshead” across at the middle section with red splotches all over it. And with this different view of the head, they assessed it to be a full seven feet across with two very small eyes about four inches above the mouth.

Then Mr. Gaines Shot It In The Head (The part about the ax comes later)

Although the gratuitous shot was fired point blank, it seemed to have had no physical effect on the creature; it simply flapped its “wings” and backed into the sea about 200 yards from shore. The explorers followed as far as they could. Then came the most astounding part, if that’s possible.

(Remember that when 10-year-old Eddie Allen had described his discovery on the previous day, he called it a “funny little fish.” This was certainly not the 150-foot monster encountered by the contingent from Delaney’s bar. But that can be explained by what followed.)

As the five men approached the surf, they spotted two “diminutive monsters which were exact counterparts of the big one.” This must have been what Eddie saw – possibly the first baby sea serpents on record, anywhere. And the big “guy” was their mother.

Brophy and Ellis managed to snare one of the smaller creatures which gave out a squeak. It was answered by the mother with something that sounded like the howl of a tiger. She lifted herself out of the water and began pulling at her beard with one of her webbed feet. That must have been quite a sight. Then things got worse.

The little one (about three feet long) finally got away. But Brophy ran back to the wagon, grabbed an ax, chased after the escapee, grabbed hold, and proceeded to hack it in half. He secured the front part, which he later sold for a dollar. The other young one swam out to its mother, climbed up on her back – and they were outta’ there.

When the adventurers returned to Delaney’s, they were, of course, laughed at. But they knew differently. Andrew Ellis even swore an affidavit asserting the truth of the matter before a Justice of the Peace. Believe it or not.

Most sea serpents have been debunked by “scientists” who profess to know better than the multitude of in-the-flesh eyewitnesses who swear by them. Skeptics have identified various serpents as a strung-out pod of narwals, a humpback whale trailing debris, a congregation of plovers, a basking shark, a giant oarfish. Or even a surviving prehistoric monster. How about simply an overgrown mutant sea snake? It’s fun to think about – from a distance.

Nessie, the Loch Ness Monster, may be a case in point. She became famous in the 1930s – and still is. The 1934 image (of the creature) is a proven fake, but people still believe. It’s estimated that the search for Nessie adds $54 million to the Scottish economy each year.

Newspaper References:

The Gloucester Sea Serpent (Ellis, R. 1994 “Monsters of the Sea” Robert Hale Ltd.)

The entire troupe jumped out of the wagon to have a better look. In Ellis’s own words: “It had a head something like that of a catfish in shape, only the mouth was V-shaped in the middle and underneath was a long reddish beard. The color of the head was a sort of fawn and right in the middle of the forehead there was a circular patch of transparent skin, which at first looked like a gigantic eye.”

But when Ellis produced a pair of opera glasses, he had a better look at that transparent patch which sat about 12 inches above the mouth. Again, in his own words:

“I could distinctly see ... the pulsating of the creature’s brain through that window of clear skin,” an interpretation verified by Mr. Gaines and Mr. Smith. Ellis went on to say that the monster sported a pair of wings or fins which, when extended, “stood out like the sails of a small yacht.”

Now the adventurers wanted an even closer view, so they started to advance “at a brisk pace.” This apparently unnerved the beast and it turned broadside to expose three webbed feet, each about three feet in diameter. The body appeared to be about “a hogshead” across at the middle section with red splotches all over it. And with this different view of the head, they assessed it to be a full seven feet across with two very small eyes about four inches above the mouth.

Then Mr. Gaines Shot It In The Head (The part about the ax comes later)

Although the gratuitous shot was fired point blank, it seemed to have had no physical effect on the creature; it simply flapped its “wings” and backed into the sea about 200 yards from shore. The explorers followed as far as they could. Then came the most astounding part, if that’s possible.

(Remember that when 10-year-old Eddie Allen had described his discovery on the previous day, he called it a “funny little fish.” This was certainly not the 150-foot monster encountered by the contingent from Delaney’s bar. But that can be explained by what followed.)

As the five men approached the surf, they spotted two “diminutive monsters which were exact counterparts of the big one.” This must have been what Eddie saw – possibly the first baby sea serpents on record, anywhere. And the big “guy” was their mother.

Brophy and Ellis managed to snare one of the smaller creatures which gave out a squeak. It was answered by the mother with something that sounded like the howl of a tiger. She lifted herself out of the water and began pulling at her beard with one of her webbed feet. That must have been quite a sight. Then things got worse.

The little one (about three feet long) finally got away. But Brophy ran back to the wagon, grabbed an ax, chased after the escapee, grabbed hold, and proceeded to hack it in half. He secured the front part, which he later sold for a dollar. The other young one swam out to its mother, climbed up on her back – and they were outta’ there.

When the adventurers returned to Delaney’s, they were, of course, laughed at. But they knew differently. Andrew Ellis even swore an affidavit asserting the truth of the matter before a Justice of the Peace. Believe it or not.

Most sea serpents have been debunked by “scientists” who profess to know better than the multitude of in-the-flesh eyewitnesses who swear by them. Skeptics have identified various serpents as a strung-out pod of narwals, a humpback whale trailing debris, a congregation of plovers, a basking shark, a giant oarfish. Or even a surviving prehistoric monster. How about simply an overgrown mutant sea snake? It’s fun to think about – from a distance.

Nessie, the Loch Ness Monster, may be a case in point. She became famous in the 1930s – and still is. The 1934 image (of the creature) is a proven fake, but people still believe. It’s estimated that the search for Nessie adds $54 million to the Scottish economy each year.

Newspaper References:

A conceptual drawing of a serpent purportedly seen off the coast of Greenland in 1734 (Hans Egede, 1734 illustration)

A conceptual drawing of a serpent purportedly seen off the coast of Greenland in 1734 (Hans Egede, 1734 illustration)