By BOB THIBAULT

World War I was over. The Armistice had been signed on November 11, 1918, and the Treaty of Versailles endorsed six months later. The Roaring Twenties were about to begin -- fueled by the infamous Eighteenth Amendment to the Constitution, which prohibited the manufacture, transport and sales of spirited beverages. The country went officially "dry" on January 17, 1920.

New Jersey’s position on the subject was pretty clear. It was the last state to ratify the amendment, and it had managed to hold off until two years after it actually went into effect. (Rhode Island never did ratify it.) One candidate for New Jersey governor in 1919, Edward I. Edwards, exclaimed, “I am as wet as the Atlantic Ocean.” He won.

Speakeasies, Stills, and Bootleggers:

Prohibition was understandably terrible for business, but many enterprising souls fought back. The answer was the ubiquitous “speakeasy.” In his remembrance of Townsend’s Inlet in the 1920s,1 Jim Doyle recalls the existence of a shed at the southwest corner of 86th Street and Landis Avenue with a sign above the door advertising “Fresh Fish.” The seafood must have been excellent because the patrons exiting the place seemed very happy.

At the other end of town, rumor has it that Twisties in Strathmere actually began in 1929 as a speakeasy, although it wasn’t called “Twisties” at the time. The windows were covered up for obvious reasons. It’s also rumored that Al Capone once stopped in, and the proprietor’s wife, Gert Charleston, loaned Mrs. Capone a dress so that she could go fishing.2

Even Cronecker’s, Sea Isle’s iconic hotel and restaurant, got into the act. There’s a story that Grandma Cronecker, when she heard the inspectors were coming, scooped up all the whiskey bottles in her apron and headed out the back door. And Margaretta Pfeiffer, who took over ownership in 1951, is reported to have said, “This bar has never been closed.”3

Meanwhile, the government had been anything but idle. Federal agents were kept busy intervening in any establishment where a whiff of whiskey was in the air. Samuel A. Vansant, Jr.4 tells of the raid of a rooming house at 36th Street and Pleasure Avenue by the Federal Alcohol and Tobacco Division. The feds arrested everybody in the place, confiscated more than two dozen containers of the good stuff, then proceeded to dump the contents into a convenient gutter, where it all somehow ended up in the meadow west of town.

By BOB THIBAULT

World War I was over. The Armistice had been signed on November 11, 1918, and the Treaty of Versailles endorsed six months later. The Roaring Twenties were about to begin -- fueled by the infamous Eighteenth Amendment to the Constitution, which prohibited the manufacture, transport and sales of spirited beverages. The country went officially "dry" on January 17, 1920.

New Jersey’s position on the subject was pretty clear. It was the last state to ratify the amendment, and it had managed to hold off until two years after it actually went into effect. (Rhode Island never did ratify it.) One candidate for New Jersey governor in 1919, Edward I. Edwards, exclaimed, “I am as wet as the Atlantic Ocean.” He won.

Speakeasies, Stills, and Bootleggers:

Prohibition was understandably terrible for business, but many enterprising souls fought back. The answer was the ubiquitous “speakeasy.” In his remembrance of Townsend’s Inlet in the 1920s,1 Jim Doyle recalls the existence of a shed at the southwest corner of 86th Street and Landis Avenue with a sign above the door advertising “Fresh Fish.” The seafood must have been excellent because the patrons exiting the place seemed very happy.

At the other end of town, rumor has it that Twisties in Strathmere actually began in 1929 as a speakeasy, although it wasn’t called “Twisties” at the time. The windows were covered up for obvious reasons. It’s also rumored that Al Capone once stopped in, and the proprietor’s wife, Gert Charleston, loaned Mrs. Capone a dress so that she could go fishing.2

Even Cronecker’s, Sea Isle’s iconic hotel and restaurant, got into the act. There’s a story that Grandma Cronecker, when she heard the inspectors were coming, scooped up all the whiskey bottles in her apron and headed out the back door. And Margaretta Pfeiffer, who took over ownership in 1951, is reported to have said, “This bar has never been closed.”3

Meanwhile, the government had been anything but idle. Federal agents were kept busy intervening in any establishment where a whiff of whiskey was in the air. Samuel A. Vansant, Jr.4 tells of the raid of a rooming house at 36th Street and Pleasure Avenue by the Federal Alcohol and Tobacco Division. The feds arrested everybody in the place, confiscated more than two dozen containers of the good stuff, then proceeded to dump the contents into a convenient gutter, where it all somehow ended up in the meadow west of town.

A raid of a rooming house at 36th Street and Pleasure Avenue was conducted by the Federal Alcohol and Tobacco Division.

Sea Isle gained its share of Prohibition infamy in an article in The Cape May County Times of January 29, 1932. The headline read: “Mastermind of Giant Still Eludes Officers; Kidnaps Pair Guarding It.”

The still in question was located in a three-story house at 43rd Place and the canal. It was capable of producing hundreds of gallons of illicit alcohol a day. Sugar was imported in two-ton loads, and coke, used to fire the huge steam boiler, was brought into town by the truckload. The man behind the enterprise was said to be “a powerful Philadelphia gangster.” A few hours after the still was uncovered, it mysteriously disappeared, along with the two officials guarding it – so with the evidence gone no one could be charged with a crime. (The kidnapped guards were later released, unharmed, in Ocean View.)

And so it went. It’s not clear just how many illegal speakeasies, stills, and attendant bootleggers thrived in the neighborhood around Sea Isle, but the answer had to be “Plenty.” It was reported that dozens of stills were uncovered in the northern part of the county, where farmers would bring their moonshine to speakeasies in resort communities buried underneath a load of apples or vegetables.5

Sea Isle seemed never to be enamored with the restrictions of Prohibition. In the only survey available (1926), 88 percent of those polled in the town favored repeal – the largest majority in Cape May County.

The Rum Runners:

All the shenanigans described above took place on solid land, where bootleggers transported their product to market using trucks, automobiles (including high-powered Stutz Bearcats), and anything else on wheels. But it was on the water and on the beach that Sea Isle City really got into the action. The infamous rum runners were the ones who got the stuff to the bootleggers. And Sea Isle provided an Ideal playground for these ship-to-shore transactions.

At the beginning of Prohibition, the limit of U.S. jurisdiction extended three miles from shore. Freighters and schooners carrying legal alcohol, mostly from Canada or the Caribbean, would anchor just beyond this limit and set up shop as floating liquor stores. Fast “contact boats” would tie up, tender large packets of cash, load up with product, then speed toward shore with their purchase. It became the job of the U.S. Coast Guard to intercept them.

A raid of a rooming house at 36th Street and Pleasure Avenue was conducted by the Federal Alcohol and Tobacco Division.

Sea Isle gained its share of Prohibition infamy in an article in The Cape May County Times of January 29, 1932. The headline read: “Mastermind of Giant Still Eludes Officers; Kidnaps Pair Guarding It.”

The still in question was located in a three-story house at 43rd Place and the canal. It was capable of producing hundreds of gallons of illicit alcohol a day. Sugar was imported in two-ton loads, and coke, used to fire the huge steam boiler, was brought into town by the truckload. The man behind the enterprise was said to be “a powerful Philadelphia gangster.” A few hours after the still was uncovered, it mysteriously disappeared, along with the two officials guarding it – so with the evidence gone no one could be charged with a crime. (The kidnapped guards were later released, unharmed, in Ocean View.)

And so it went. It’s not clear just how many illegal speakeasies, stills, and attendant bootleggers thrived in the neighborhood around Sea Isle, but the answer had to be “Plenty.” It was reported that dozens of stills were uncovered in the northern part of the county, where farmers would bring their moonshine to speakeasies in resort communities buried underneath a load of apples or vegetables.5

Sea Isle seemed never to be enamored with the restrictions of Prohibition. In the only survey available (1926), 88 percent of those polled in the town favored repeal – the largest majority in Cape May County.

The Rum Runners:

All the shenanigans described above took place on solid land, where bootleggers transported their product to market using trucks, automobiles (including high-powered Stutz Bearcats), and anything else on wheels. But it was on the water and on the beach that Sea Isle City really got into the action. The infamous rum runners were the ones who got the stuff to the bootleggers. And Sea Isle provided an Ideal playground for these ship-to-shore transactions.

At the beginning of Prohibition, the limit of U.S. jurisdiction extended three miles from shore. Freighters and schooners carrying legal alcohol, mostly from Canada or the Caribbean, would anchor just beyond this limit and set up shop as floating liquor stores. Fast “contact boats” would tie up, tender large packets of cash, load up with product, then speed toward shore with their purchase. It became the job of the U.S. Coast Guard to intercept them.

Rum runners transferred the goods from a schooner to a small boat that took the liquor onshore. (Photo courtesy U.S. Coast Guard)

There were two major problems with this scenario. First, there were a limited number of Coast Guard picket boats along the Cape May County coast, stationed primarily at the county’s many inlets. But it was estimated (by a rum runner himself) that it would have taken 60 such boats to do the job. Second, at least in the beginning, the Coast Guard craft were much slower, so they were consistently being outrun by the rum runners.

To add to their already significant advantage, rum runners would employ some sneaky tricks. They’d send an empty decoy boat racing toward shore to divert the Coast Guard’s attention. They’d use boats with hidden chambers and false bottoms. They’d tow alcohol underneath in waterproof containers. They’d hide their product in extraneous objects such as bibles and children’s toys. They’d set their liquor adrift to float in on the tide and be scooped up by a waiting bootlegger.

The rum runners even invoked technology. Bottles were encased in salt and deposited in water near the beach. When the salt dissolved, the bottles bobbed to the surface into the hands of the bootleggers. And if all else failed, they could simply set their boat on fire to destroy the evidence.

Rum runners transferred the goods from a schooner to a small boat that took the liquor onshore. (Photo courtesy U.S. Coast Guard)

There were two major problems with this scenario. First, there were a limited number of Coast Guard picket boats along the Cape May County coast, stationed primarily at the county’s many inlets. But it was estimated (by a rum runner himself) that it would have taken 60 such boats to do the job. Second, at least in the beginning, the Coast Guard craft were much slower, so they were consistently being outrun by the rum runners.

To add to their already significant advantage, rum runners would employ some sneaky tricks. They’d send an empty decoy boat racing toward shore to divert the Coast Guard’s attention. They’d use boats with hidden chambers and false bottoms. They’d tow alcohol underneath in waterproof containers. They’d hide their product in extraneous objects such as bibles and children’s toys. They’d set their liquor adrift to float in on the tide and be scooped up by a waiting bootlegger.

The rum runners even invoked technology. Bottles were encased in salt and deposited in water near the beach. When the salt dissolved, the bottles bobbed to the surface into the hands of the bootleggers. And if all else failed, they could simply set their boat on fire to destroy the evidence.

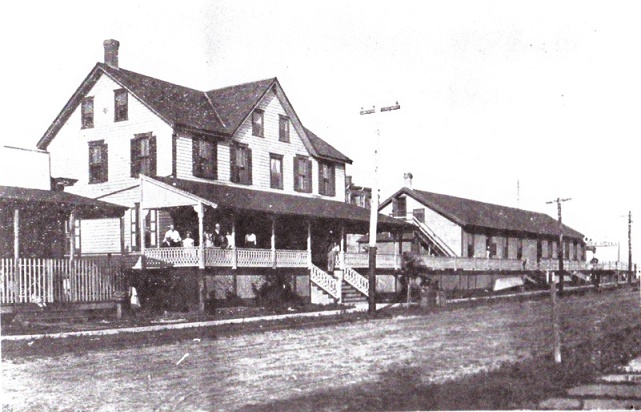

Life-saving crews, such as the one pictured at Townsend’s Inlet, supplemented the work of guarding the shore, but they were simply overrun by the numbers.

After the usual politicking, the Twenty-First Amendment was finally ratified on December 5, 1933. Section 1 simply states: “The eighteenth article of amendment to the Constitution of the United States is hereby repealed.” That says it all.

Folks could imbibe again without looking over their shoulders. Rum runners were out of business. Bootleggers and other criminals, the ones not already in jail, were forced to look elsewhere. Doctors could stop prescribing “medicinal whiskey.” And the Coast Guard could go back to guarding the coast.

New Jersey had once again made its preference clear; it was the fifth state to ratify the amendment. The vote was 202 to 2. In Cape May County, the vote for delegates to the Constitutional Convention ran 78 percent in favor of repeal.

President Franklin D. Roosevelt put it pretty succinctly when he said: “What America needs now is a drink.”

To learn more about the 1920s era in Sea Isle, and to browse through a collection of photos, literature, and artifacts, visit the Sea Isle City Historical Museum at 48th Street and Central Avenue. Access the website at www.seaislemuseum.com. Call 609-263-2992. Current hours are 10 a.m. to 3 p.m. Monday, Tuesday, Thursday, and Friday, and 10 a.m. to 1 p.m. Saturday.

Life-saving crews, such as the one pictured at Townsend’s Inlet, supplemented the work of guarding the shore, but they were simply overrun by the numbers.

After the usual politicking, the Twenty-First Amendment was finally ratified on December 5, 1933. Section 1 simply states: “The eighteenth article of amendment to the Constitution of the United States is hereby repealed.” That says it all.

Folks could imbibe again without looking over their shoulders. Rum runners were out of business. Bootleggers and other criminals, the ones not already in jail, were forced to look elsewhere. Doctors could stop prescribing “medicinal whiskey.” And the Coast Guard could go back to guarding the coast.

New Jersey had once again made its preference clear; it was the fifth state to ratify the amendment. The vote was 202 to 2. In Cape May County, the vote for delegates to the Constitutional Convention ran 78 percent in favor of repeal.

President Franklin D. Roosevelt put it pretty succinctly when he said: “What America needs now is a drink.”

To learn more about the 1920s era in Sea Isle, and to browse through a collection of photos, literature, and artifacts, visit the Sea Isle City Historical Museum at 48th Street and Central Avenue. Access the website at www.seaislemuseum.com. Call 609-263-2992. Current hours are 10 a.m. to 3 p.m. Monday, Tuesday, Thursday, and Friday, and 10 a.m. to 1 p.m. Saturday.

“Spotlight on History” References

1. Townsend’s Inlet in the Twenties (Memories of a Childhood) by Jim Doyle, c1992 2. TwistiesTavern.com 3. The Evening Bulletin, 8 August 1951 4. The Story of a History of Sea Isle City & Townsend Inlet by Samuel A. Vansant, Jr., 1993 5. Down Memory Lane by Bill Robinson, Herald Newspapers, 20 April 1994 This “Spotlight on History” was written by Sea Isle City Historical Society volunteer Bob Thibault. Unless otherwise noted, photos were provided courtesy of the Sea Isle City Historical Museum.